ECOSYSTEMS

The Dying Cavendish

Rachelle Mozman Solano

This section explores the environmental impact of bananas in the areas of Latin America and the Caribbean where they are grown. By addressing issues such as the landscape transformations caused by the mass planting of bananas, the serious health consequences of working in the banana industry and the symbolic position held by bananas in Latin American visual culture, numerous artists have reflected on the traces that this fruit has left in the ecosystems of banana producing countries throughout the last two centuries.

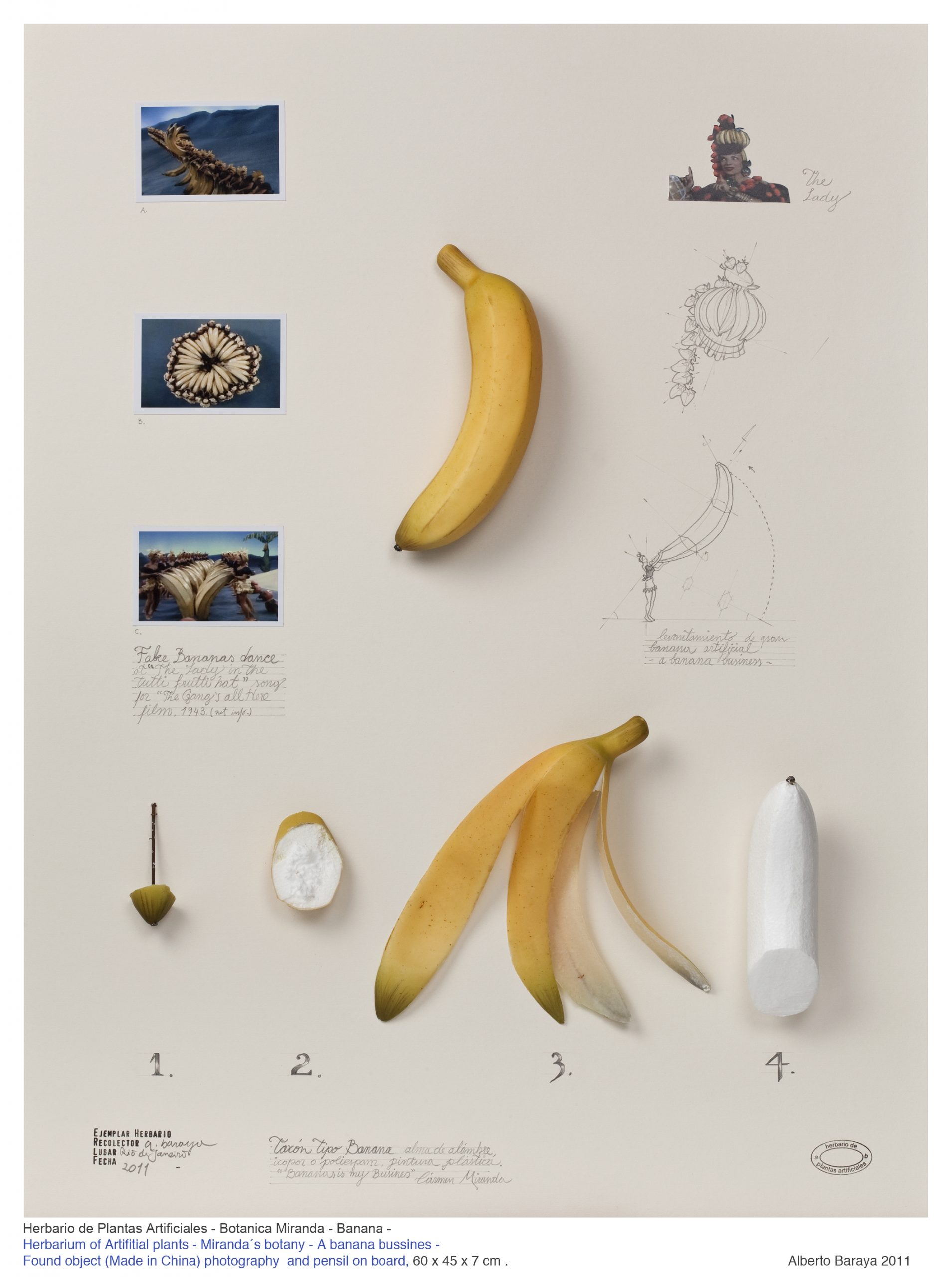

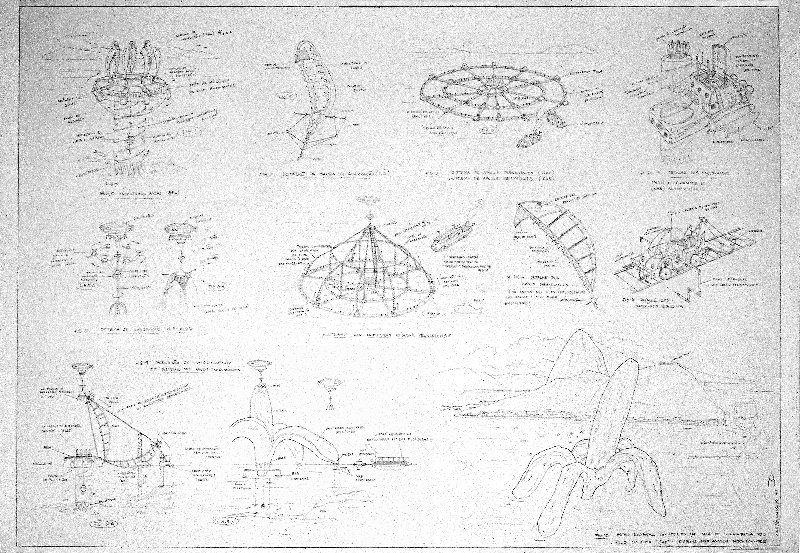

The size of the international banana market has a serious impact on the social ecosystem in the communities that grow the fruit, especially in those countries whose national economies largely depend on banana production. Ecuador, for example, is the world’s largest banana exporter, with the industry accounting for around 20% of GDP and providing, directly and indirectly, approximately half a million jobs.1 The fact that the banana market is dominated by a monopoly of a few multinationals coupled with the influence held by the supermarkets led to a downward price war, leaving farmers with tiny profit margins. This encourages temporary work and undermines any association or unionisation of workers (whose difficult working conditions include working 14 hours a day, 6 days a week in very high temperatures), blocking any fair trade growth.2 The global banana market therefore affects the ecosystem in the communities growing the fruit, disrupts the distribution of resources and causes profound inequalities between producers and consumers. In his work, Alberto Baraya draws on the European Enlightenment’s own classification techniques to highlight the unsustainability of capitalism and to illustrate the parallels between extracting natural resources and exploiting workers as elements from the same system where life is treated as an economic resource.

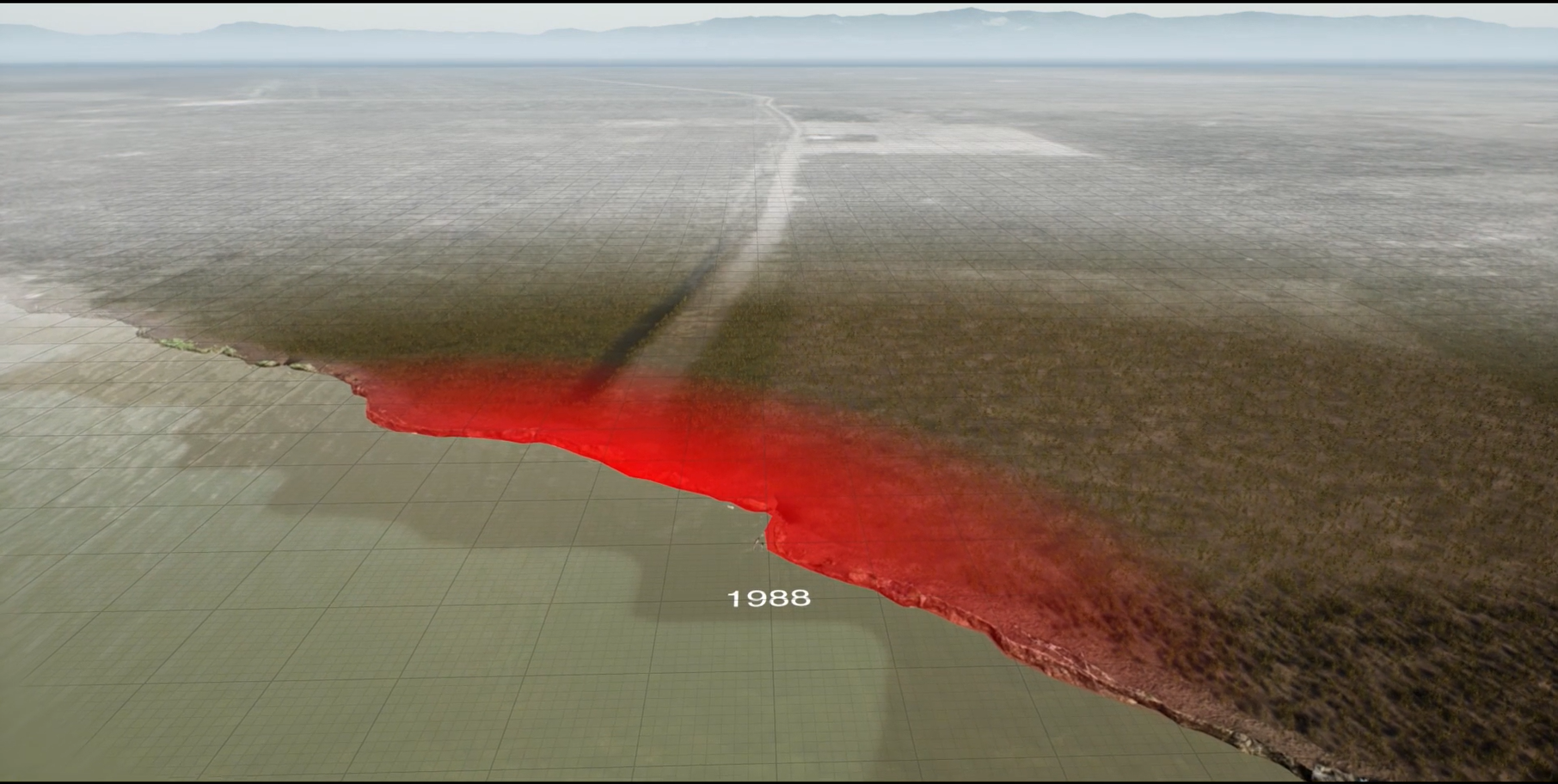

The biological ecosystem on banana plantations—that is to say, the habitat in the regions where bananas are grown on a large scale—has been seriously affected by the increasing use of monoculture practices. In the first half of the 20th century, the most consumed variety was the Gros Michel (musa acuminata) but following infection by a fungus called Panama disease, it was replaced by the Cavendish banana (musa cavendishii), smaller and less tasty than other varieties but capable of surviving international transport. Since 2019, the Cavendish banana has also been threatened by Panama disease and it is estimated that 10,000 hectares of the crop have already been lost.3 Monoculture damages ecosystem diversity by displacing other crops and, as a result, reduces the Global South’s agro-cultural wealth. However, a large number of farmers currently depend on monoculture for their survival and the Cavendish banana has become an important part of their diet. Rachelle Mozman Solano reflects on monoculture in her satirical film The Dying Cavendish, which was based on Minor Keith, the railway tycoon and founder of the United Fruit Company.

The use of pesticides to control Panama disease and other diseases that affect bananas has meant that the banana industry is second only to cotton growing as the world’s largest consumer of agrochemical products.4 Moreover, some of these products are classified as damaging to health by the World Health Organisation.5 These pesticides have caused widespread respiratory illnesses in the communities living around the banana plantations and they are also the reason for high infertility rates across these regions. In several of his works, Óscar Figueroa works with blue plastic bags that have been sprayed with pesticide. Bananas covered by these bags are a common sight on the industrial plantations. In Apuntes conceptuales sobre el extractivismo bananero en Barú, Milko Delgado pays tribute to those Panamanians whose health has been affected by the pesticide spraying by portraying them on the banana stickers.

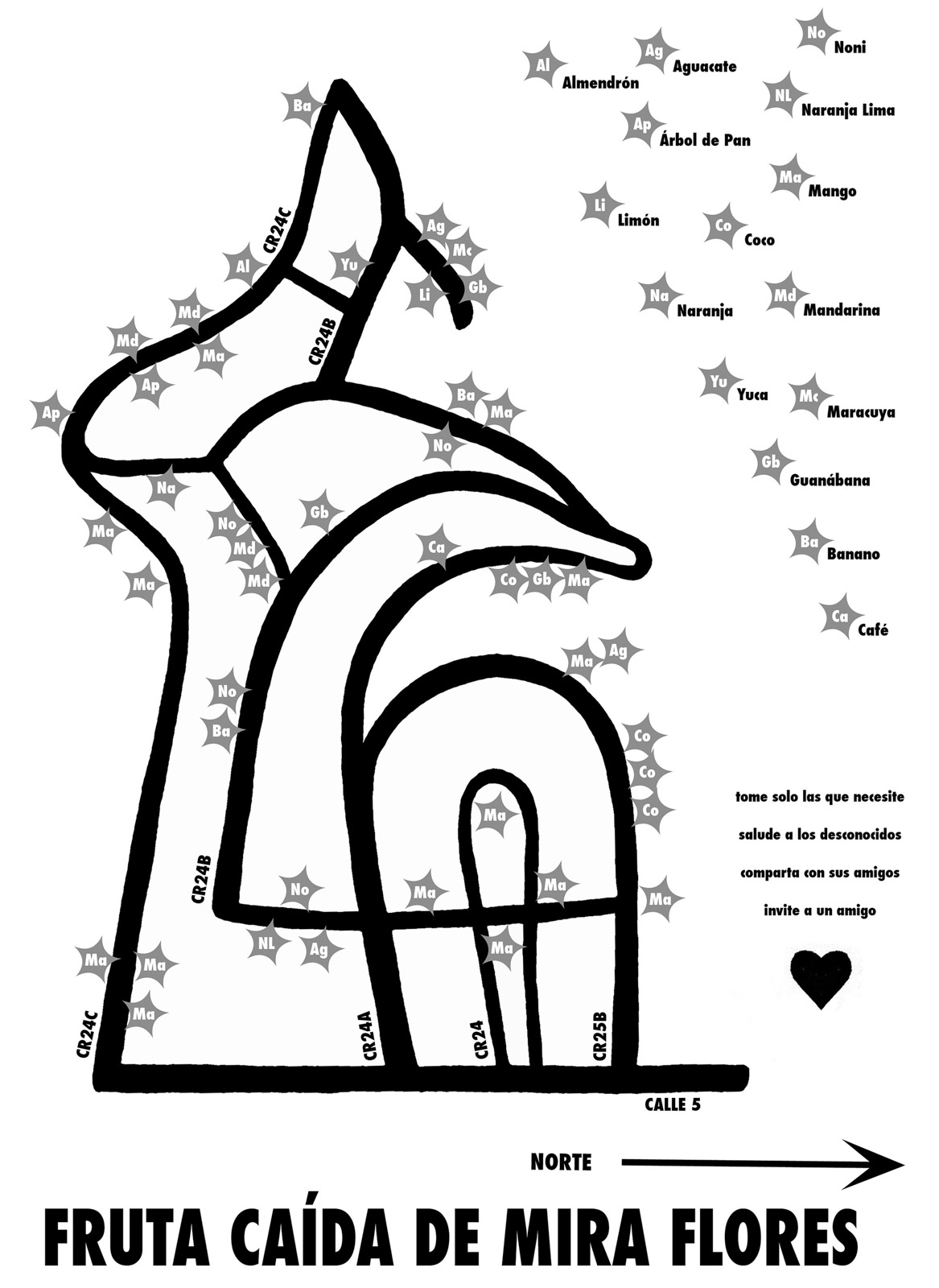

The countryside around the banana plantations is also home to traditional ways of life that are now at risk of disappearing and the way they are depicted plays a part in shaping the stories about nature and culture in these places. María Buenaventura contrasts ways of managing resources and ways of knowing by comparing orchards in the communities in areas of Colombia that were previously occupied by FARC to a bookless library that the state provided for the region. In her paintings of the musa paradisiaca, Gabriela Bettini links ecology and feminism to reflect on how Latin America has been perceived in Europe throughout history, from colonial times to the modern day, while also paying tribute to women in the worlds of botany, science and exploration.

Finally, some works in this section, such as those by Wilfredo Prieto and Adriana Lara, use the banana to reflect on the museum as an ecosystem. In these pieces, the banana is both a conceit and a readymade; a fruit which, on the one hand, alludes to Latin American art’s place in the global art market and, on the other, enables criticism of the role played by institutions in the commodification of culture.

1| Fruchthandel Magazin Ecuador Special (2020): 6.

2| “The Problem with Bananas”, Banana Link, accessed on 13 May 2021, https://www.bananalink.org.uk/the-problem-with-bananas/.

3| “Enfermedad que ataca al banano pone en alerta a productores ticos”, Corbana, accessed on 13 May 2021, https://www.corbana.co.cr/enfermedad-que-ataca-al-banano-pone-en-alerta-a-productores-ticos/.

4| “The Problem with Bananas”.

5| “The Problem with Bananas”.