VIOLENCES

Apuntes conceptuales sobre el extractivismo bananero en Barú.

Milko Delgado

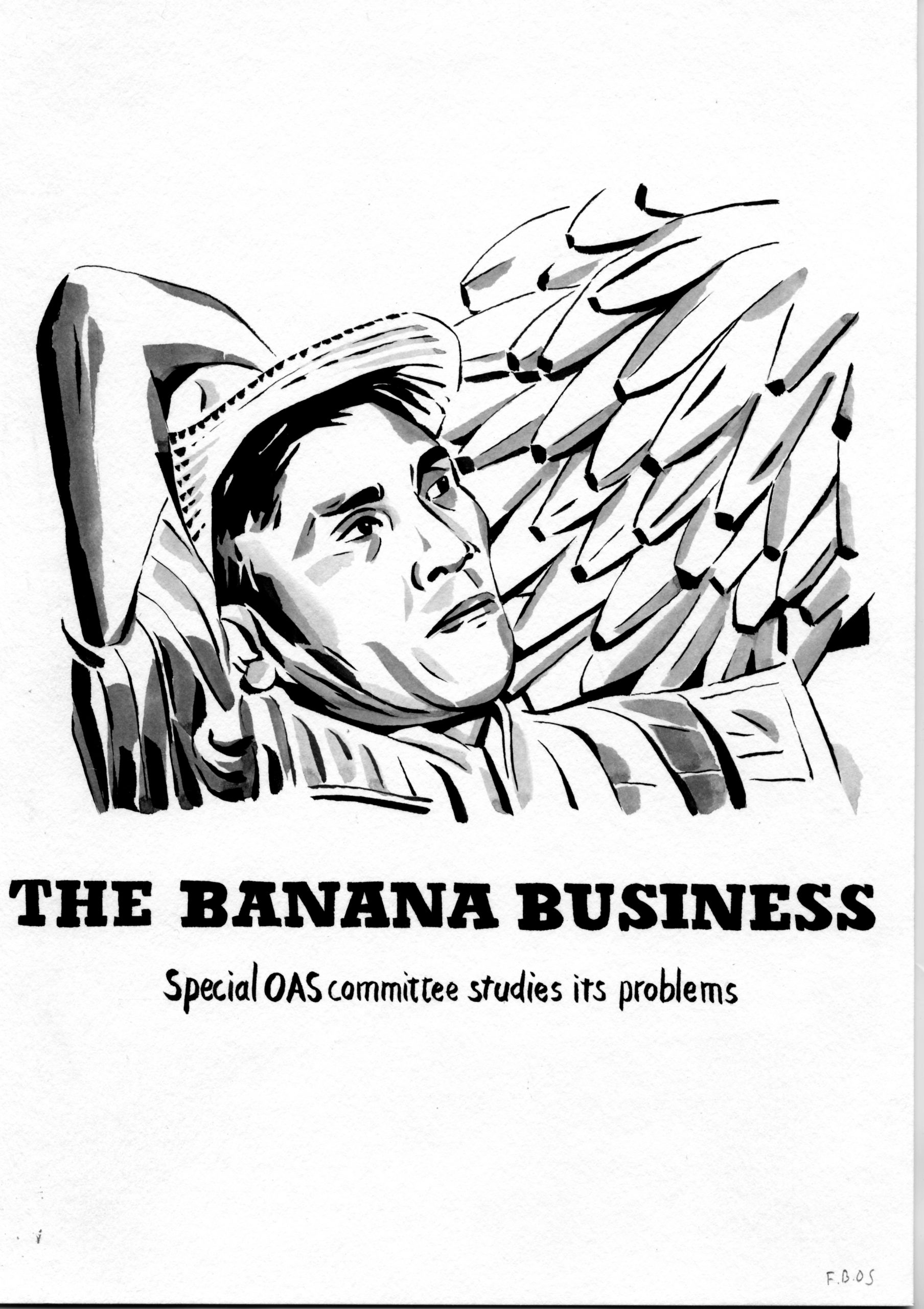

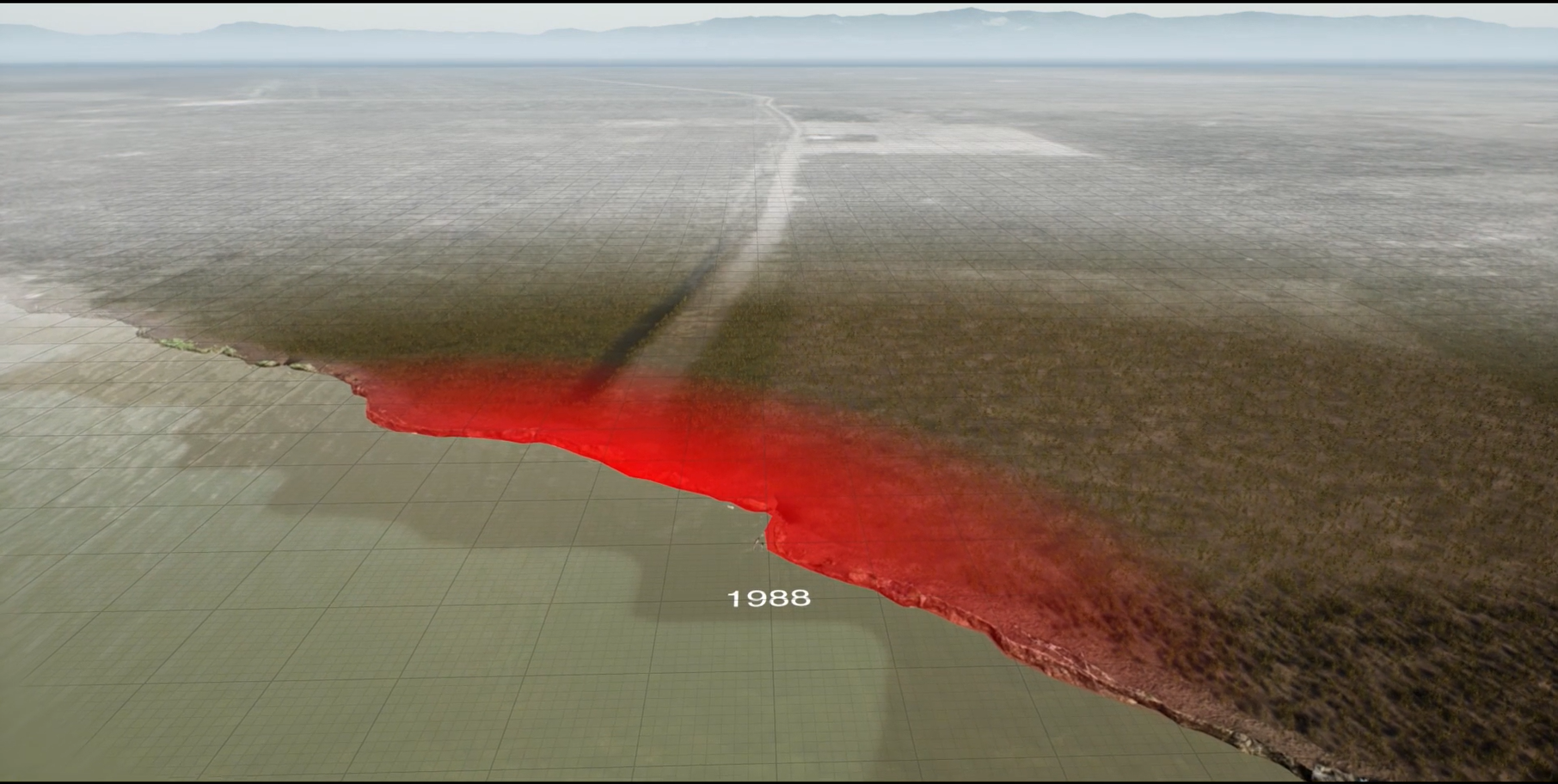

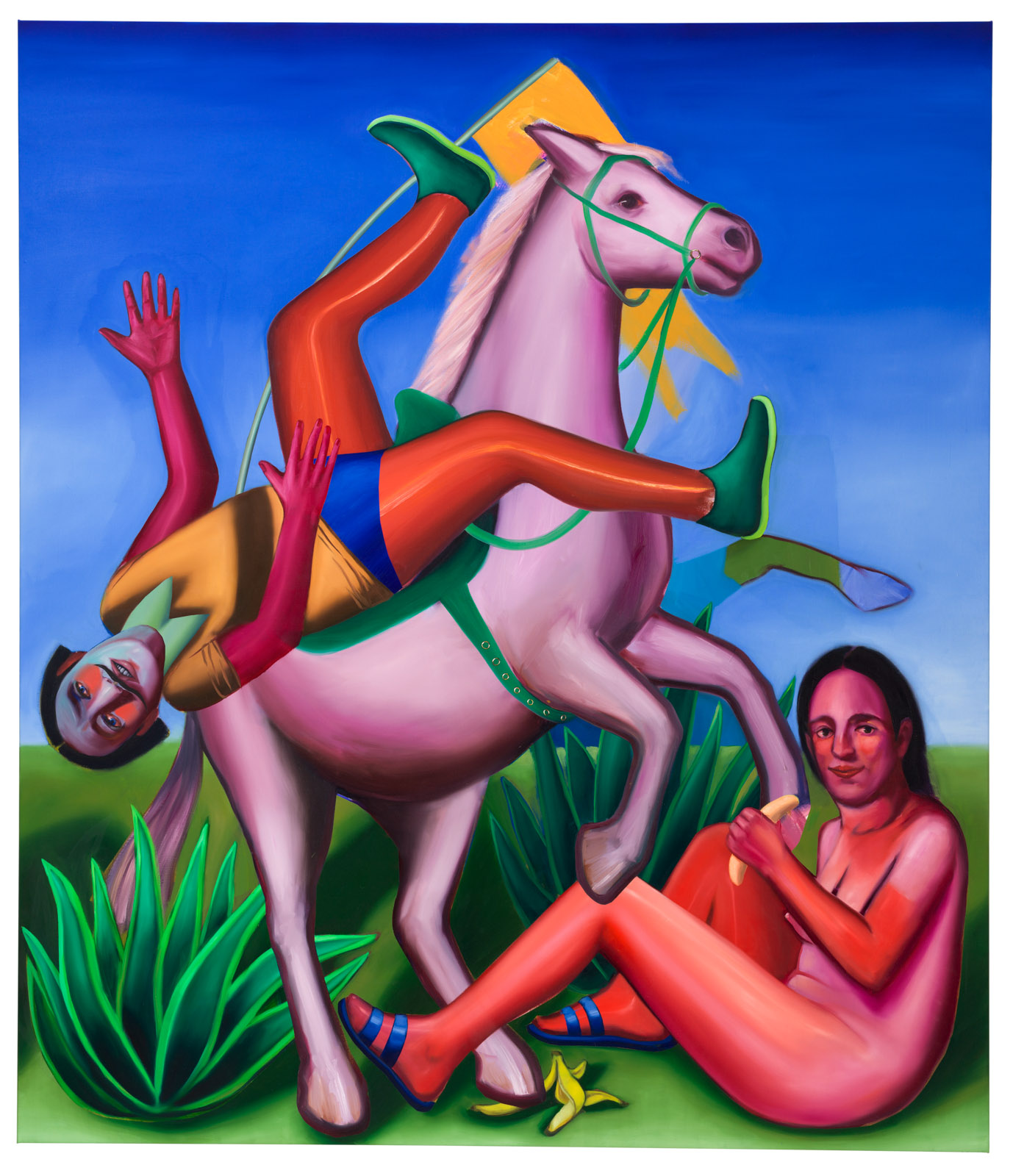

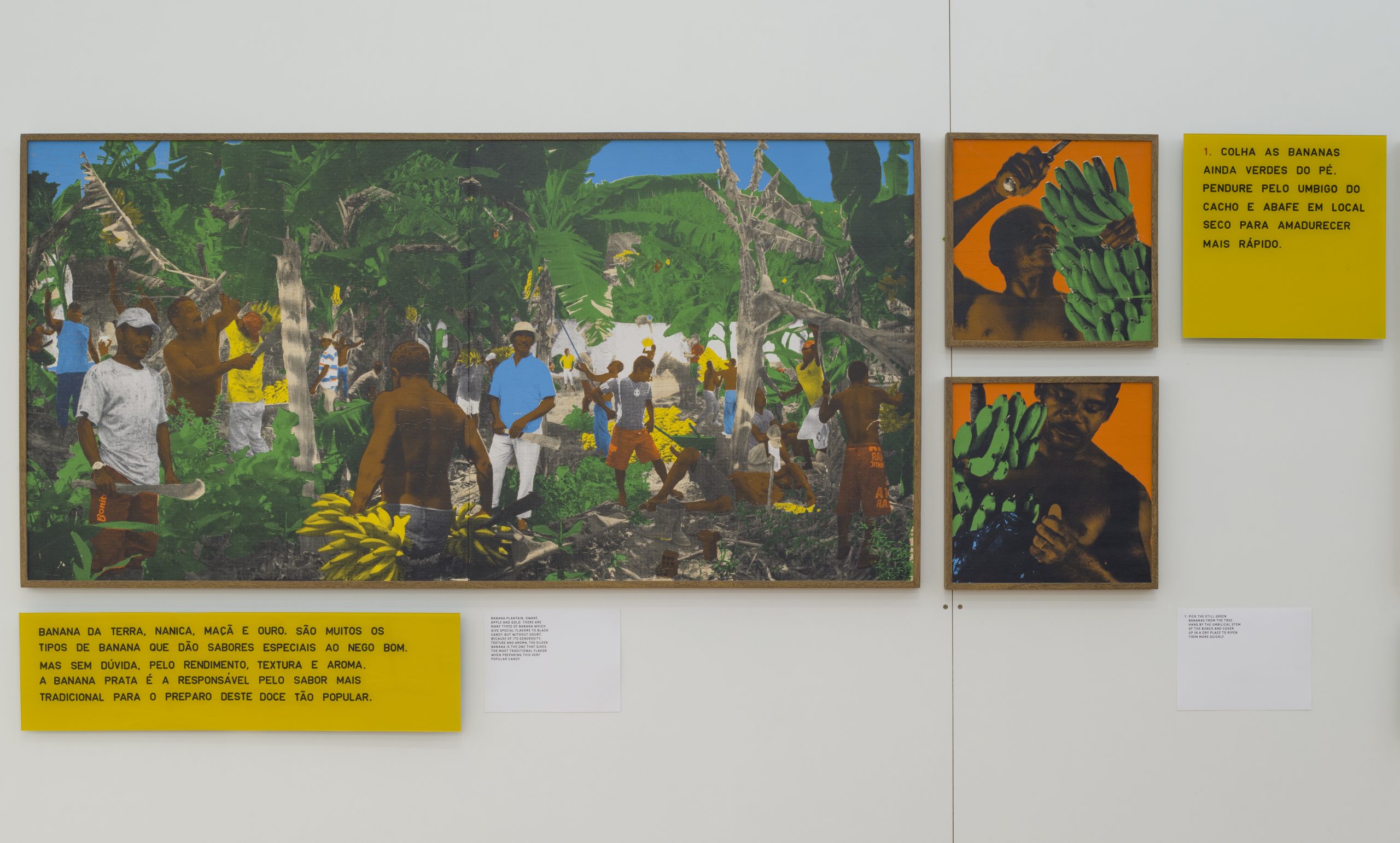

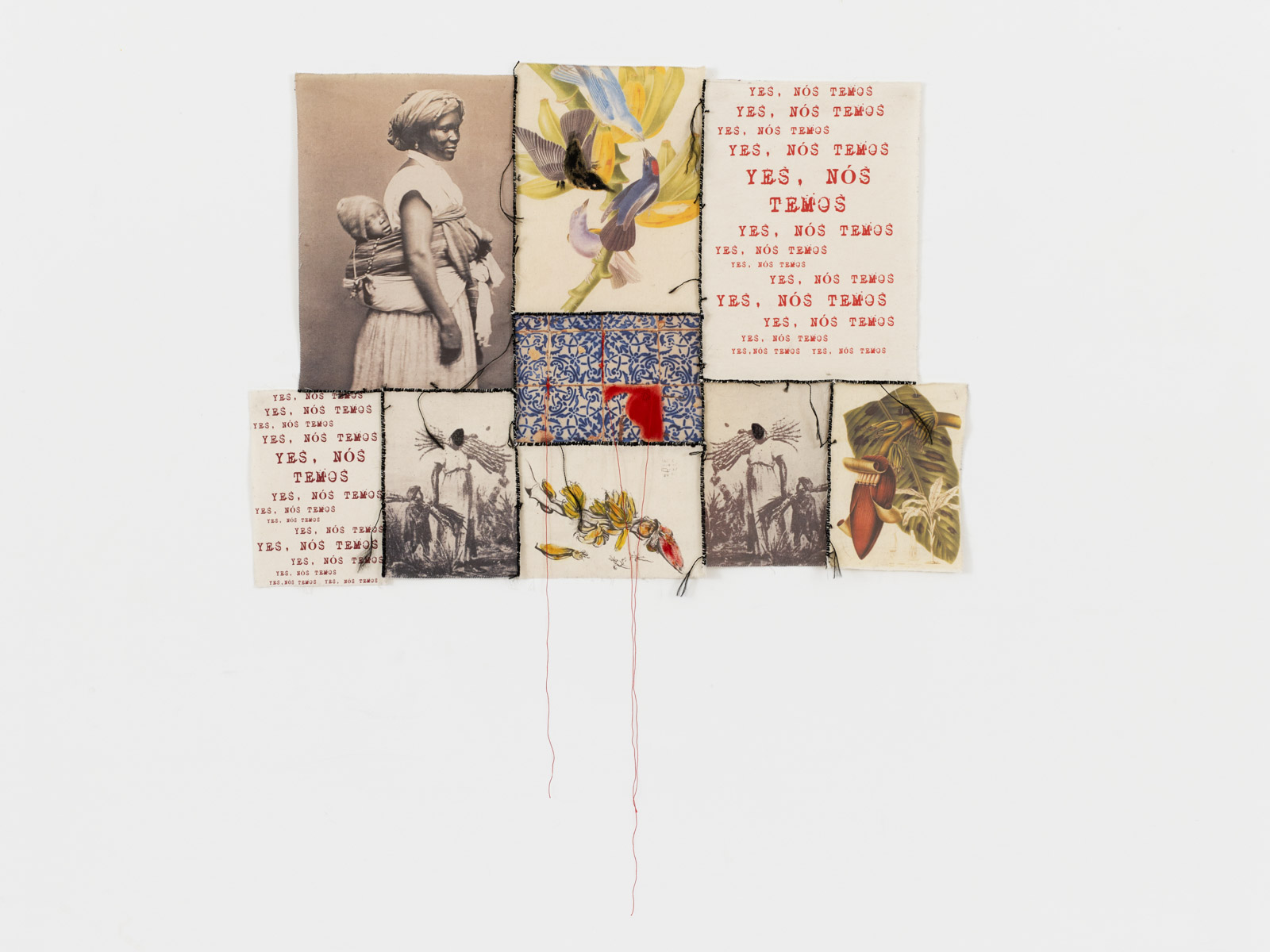

The banana, a seemingly innocuous fruit, has been the cause of a long history of violence on the American continent principally perpetrated by multinational foreign corporations and corrupt states in the regions where banana enclaves have been established. Although the story differs according to the context of each region, the establishment of plantations has followed certain patterns that have allowed the economic development of banana exportation. Although at first it was thought that these projects would encourage local progress, the human cost was very high, and it did not lead to the establishment of democratic governments in any sense nor to modernisation based on fair and equitable working relations.1 What is certain is that the establishment of banana enclaves involved not only the construction of infrastructures for the transport of fruit (such as railways, ports and roads) and the integration of isolated zones with global markets, but also the transformation of tropical forests, labour abuses, the spread of diseases and the death of hundreds of local workers. The artworks that are grouped in this section respond specifically to the tensions between the promise of progress and the violent reality of the banana plantations.

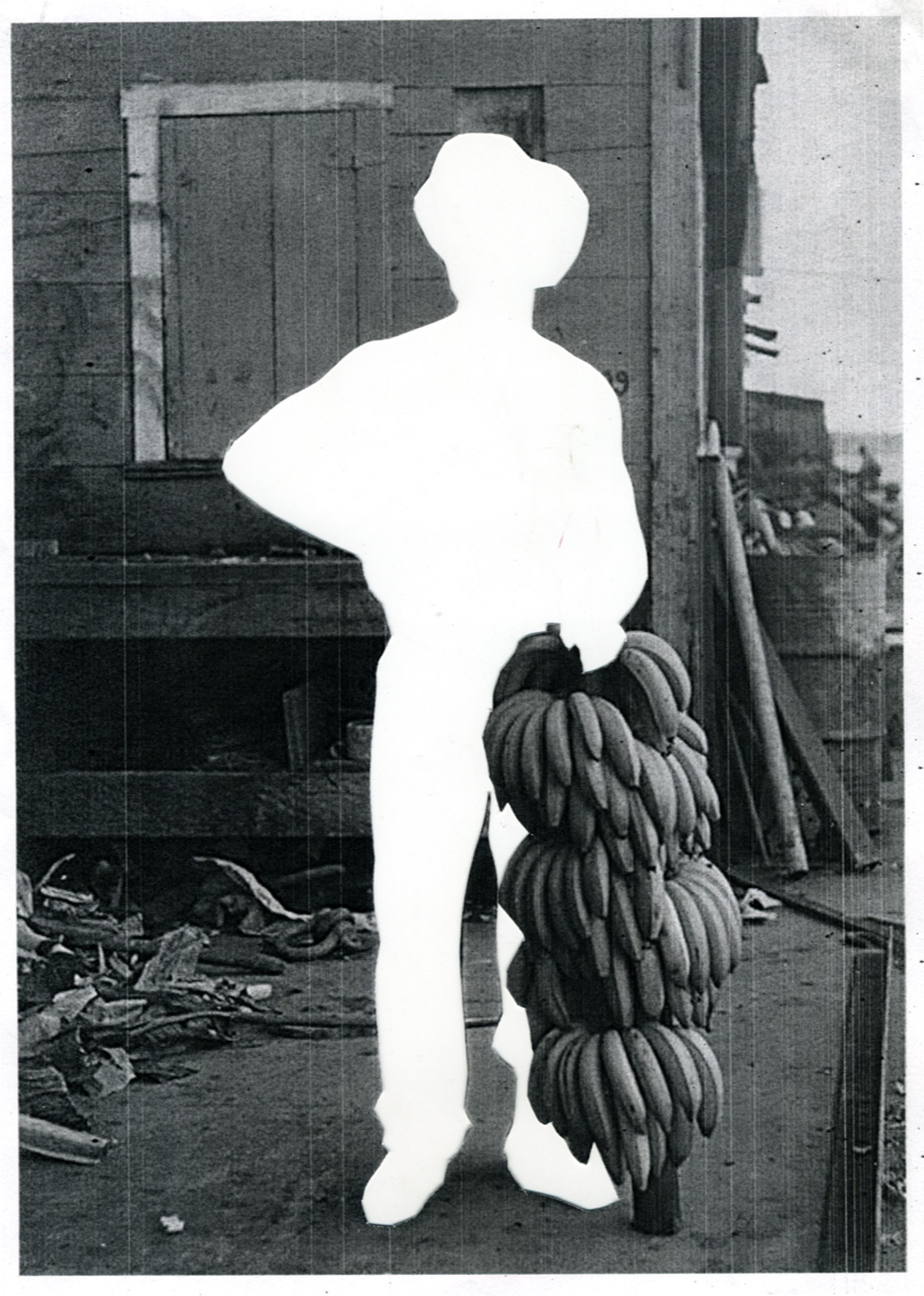

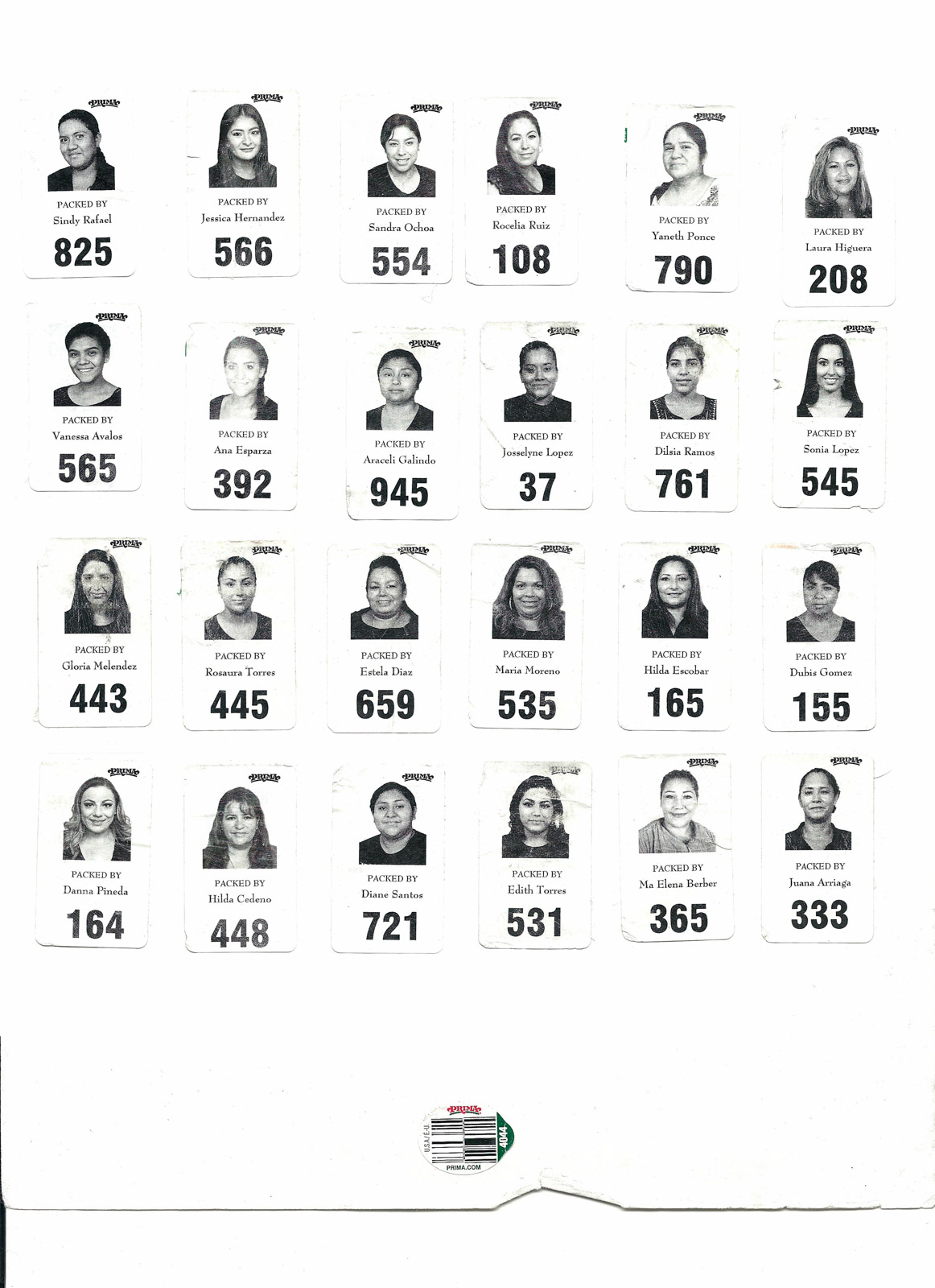

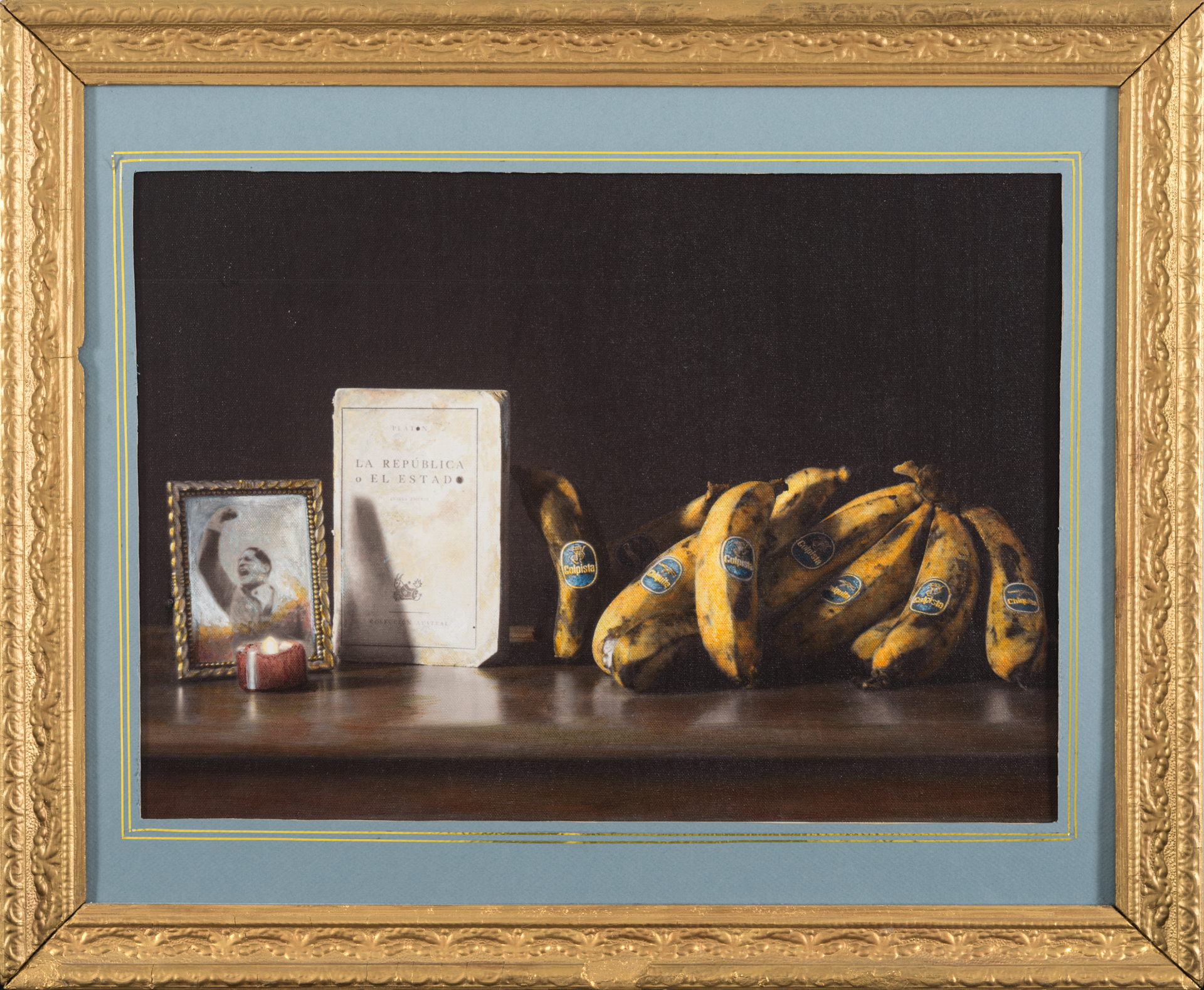

Works like those of Leandro Katz, Milko Delgado, Óscar Figueroa and Minerva Cuevas relate the presence of multinational fruit companies to workplace exploitation, low salaries and lack of sanitary provisions to protect the workers and growers and denounce the complicity of local elites. Bananas are a fruit that must be cut off the plant manually; the bunches must also be transported carefully to the cleaning and packing zone so as not to damage the fruit. To achieve this, the industry inevitably requires human labour, but the workers cannot count on the protection that would enable their bodies to tolerate this arduous work; the sanitary conditions are alarming, and the remuneration is scarcely even symbolic.2

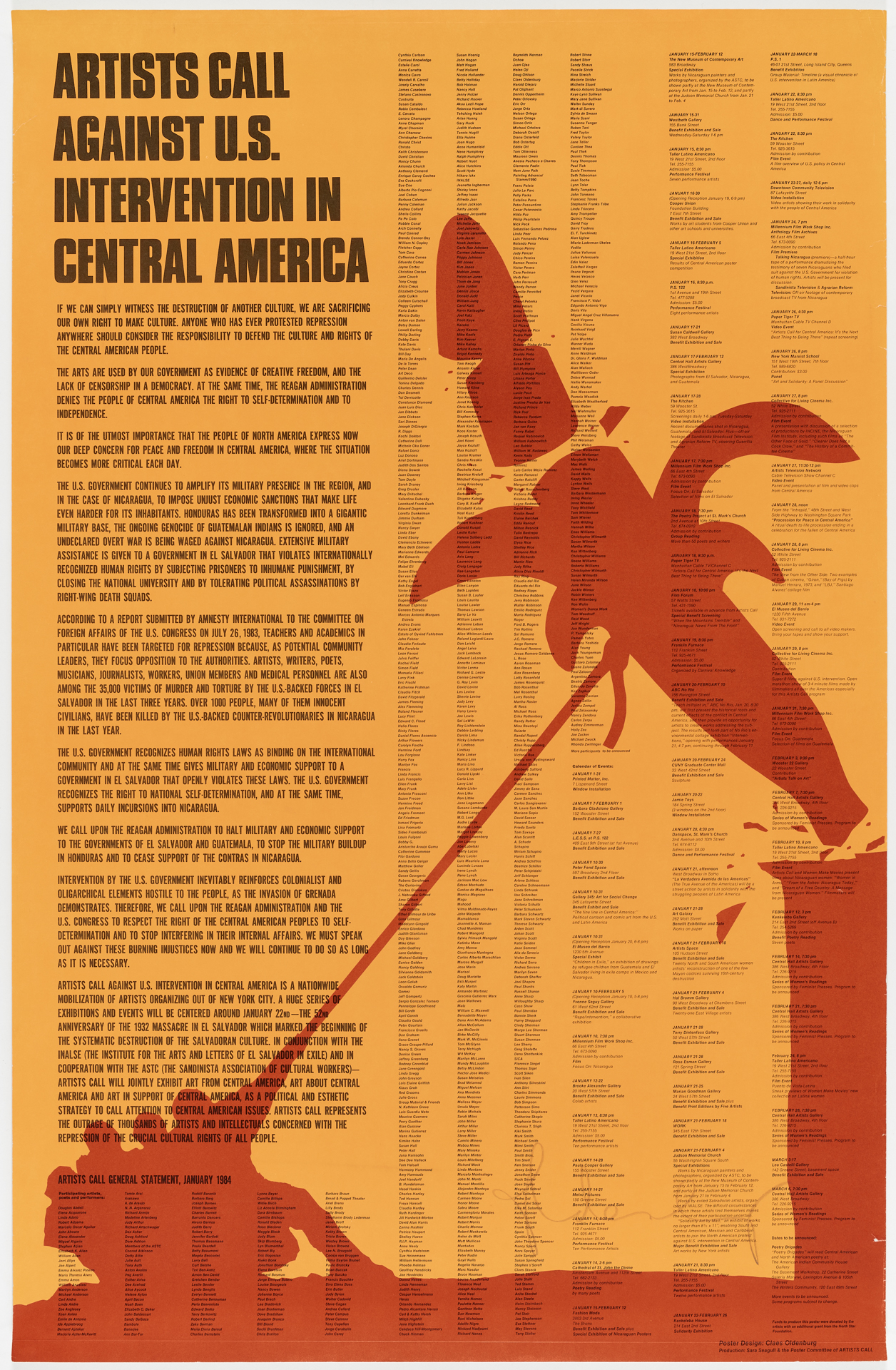

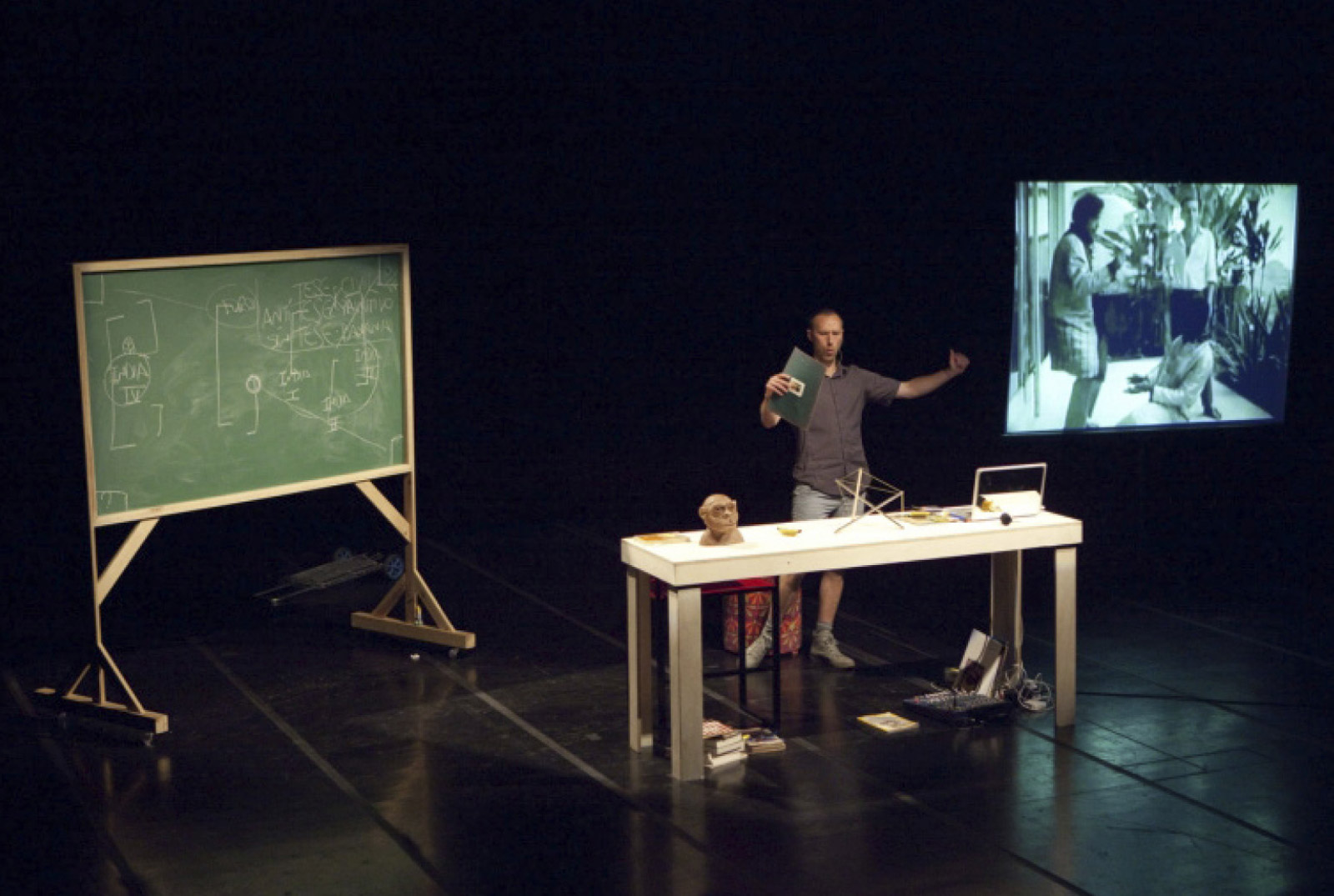

Unfair working conditions were the precise motivation for the strike that took place in 1928 in the Colombian Caribbean which culminated in the event that is known today as the Masacre de las bananeras (banana plantation massacre). The United Fruit Company workers were demanding the abolition of the contractor system, a rise in salary, a paid day of rest on Sundays, compensation for accidents and the construction of decent housing.3 The banana company rejected their petitions relying on a recent law that denied any demands from workers through strike action or any other type of “use of force”.4 The distorted news that reached the capital associated the strikers with communist agitators who wanted to assassinate the directors of the UFC and resulted in a military response. The workers reacted to the presence of the army which responded by killing hundreds of persons including women and children.5 The works of artists such as José Alejandro Restrepo, François Bucher, Doris Salcedo and Elkin Calderón, amongst others, respond to and commemorate one of the most salient episodes of violence in the collective memory of the country.

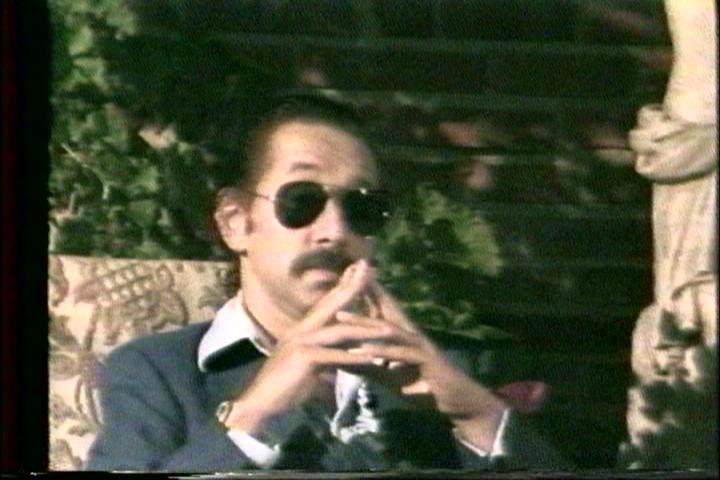

The role of states, and in particular of dictatorships, was fundamental to the establishment of the multinationals’ power in the banana enclaves. The figure of the dictator is a common denominator in several works in this section. The work of artists like David Lamelas, Roberto Guerrero, Fernando Bryce, Romy Pocztaruk, Antonio Henrique Amaral and Voluspa Jarpa examine the role of dictatorships as accomplices and perpetrators of the violence in different contexts in Latin America. The alliances established between the corrupt states and the multinational banana companies bolstered some of these dictatorships, as happened in Guatemala when the president Juan Jacobo Árbenz was deposed in 1954 in a coup d’état executed by the CIA and directed by the government of the USA in alliance with the United Fruit Company.6 In a context such as Brazil, the dictatorship was the excuse for torturing and persecuting citizens whose identity was associated with the lush tropics, often represented by the banana fruit.

Political instability, poverty and the dependency of the economies of the region on extracted products indeed led to the establishment of the term “Banana Republic”, an idea that obviously obscures the decisive role played by multinationals such as the United Fruit Company and the Standard Fruit Company in political, economic and cultural conflicts in these territories. The works of artists such as Jaime Tarazona, Leonardo González and Luis Camnitzer question these stereotypes and reflect on the implications and complexities behind this term. Through the contemporary lens, artists principally from those countries that have suffered the most powerful phenomena of violence respond through their works to a past whose consequences are still alive today.

1| Steve Striffler y Mark Moberg, “Introduction”, en Banana Wars: Power, Production and History in the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 4.

2| Según Banana Link los trabajadores en las bananeras reciben entre el 4 y el 9% del valor total de la fruta. “All About Bananas”, Banana Link, consultado el 27 de mayo de 2021, https://www.bananalink.org.uk/all-about-bananas/.

3| “La masacre de las bananeras”, Red Cultural del Banco de la República, consultado el 4 de mayo de 2021, https://www.banrepcultural.org/biblioteca-virtual/credencial-historia/numero-190/la-masacre-de-las-bananeras.

4| “La masacre de las bananeras”.

5| “La masacre de las bananeras”.

6| Para un recuento detallado de este episodio, ver: Roberto García Ferreira, “La CIA y el exilio de Jacobo Árbenz”. Perfiles Latinoamericanos 13, no. 28 ( 2006): 59-82.