IDENTITIES

No Title

Victoria Cabezas

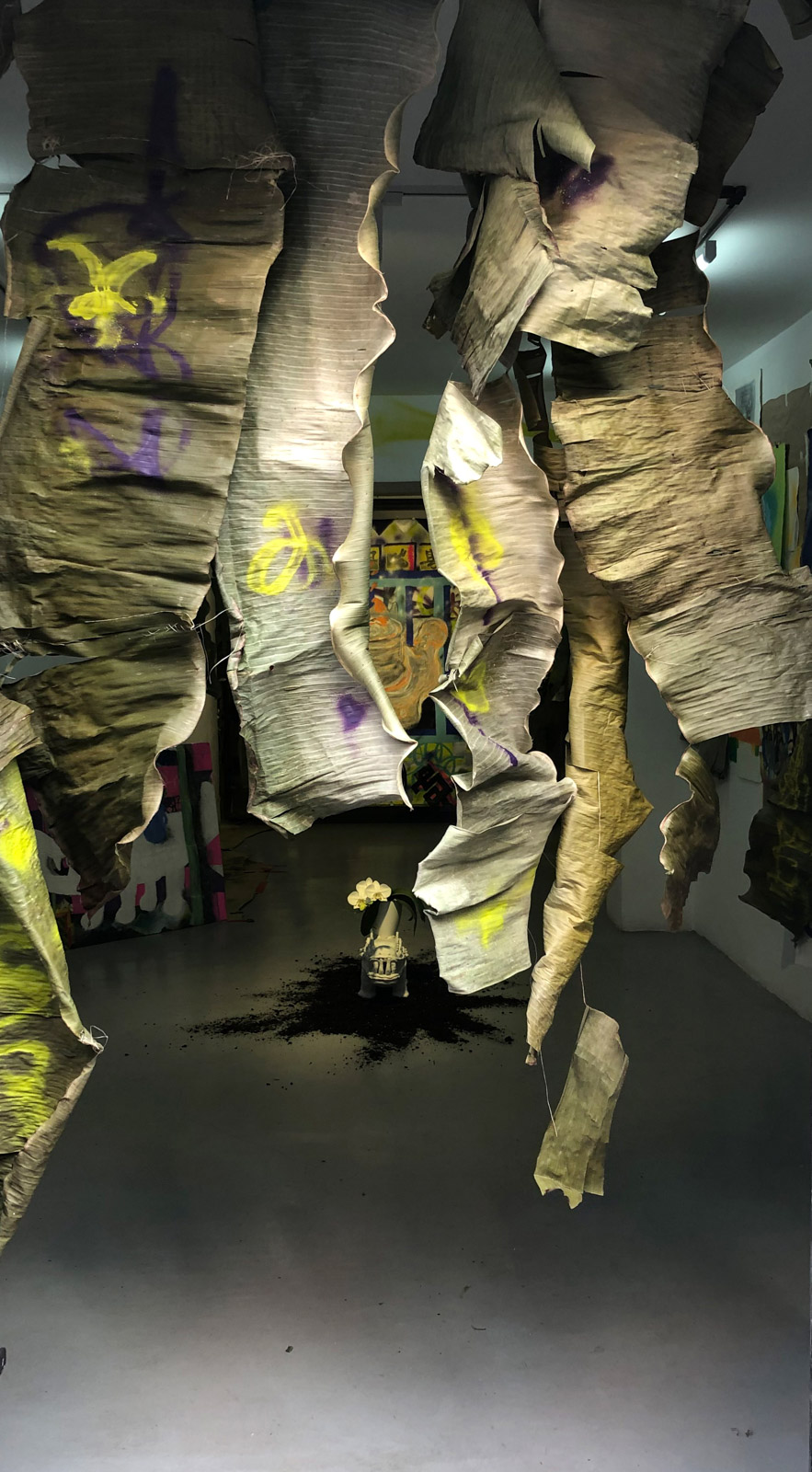

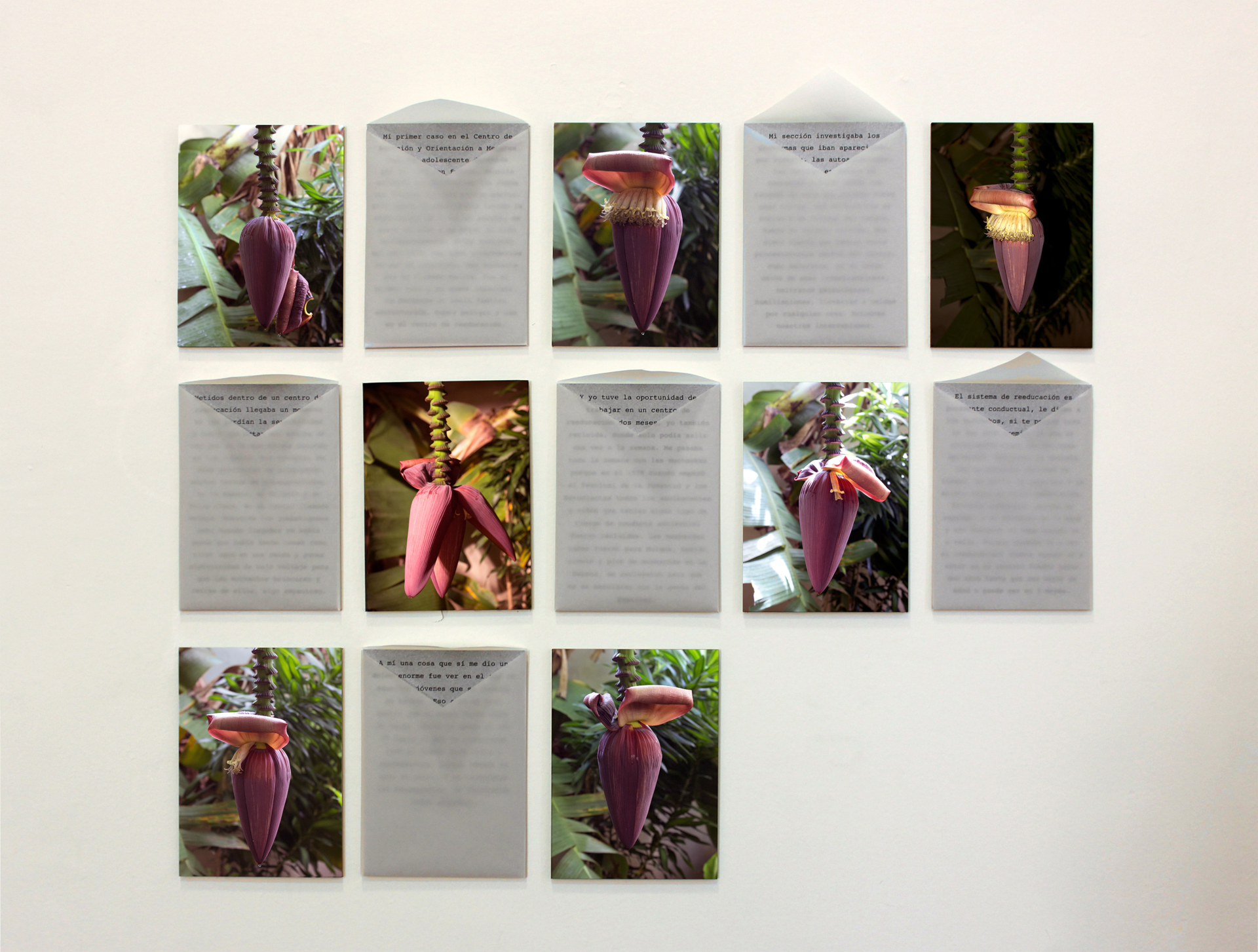

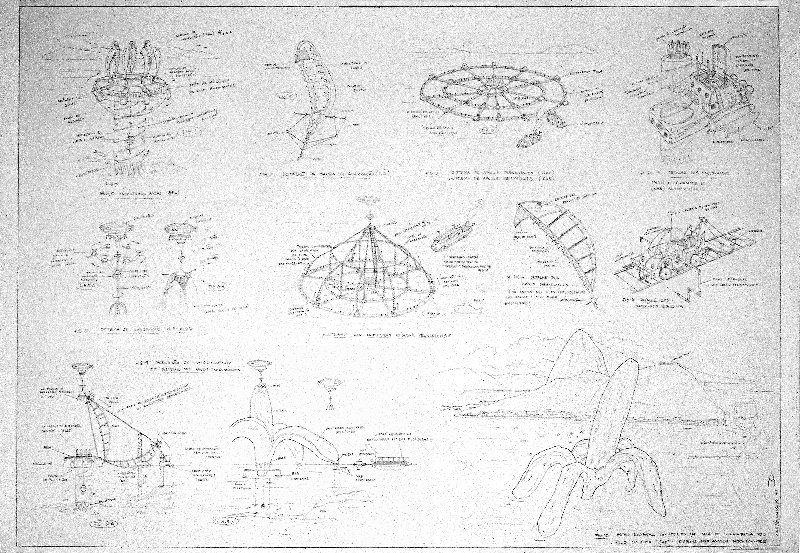

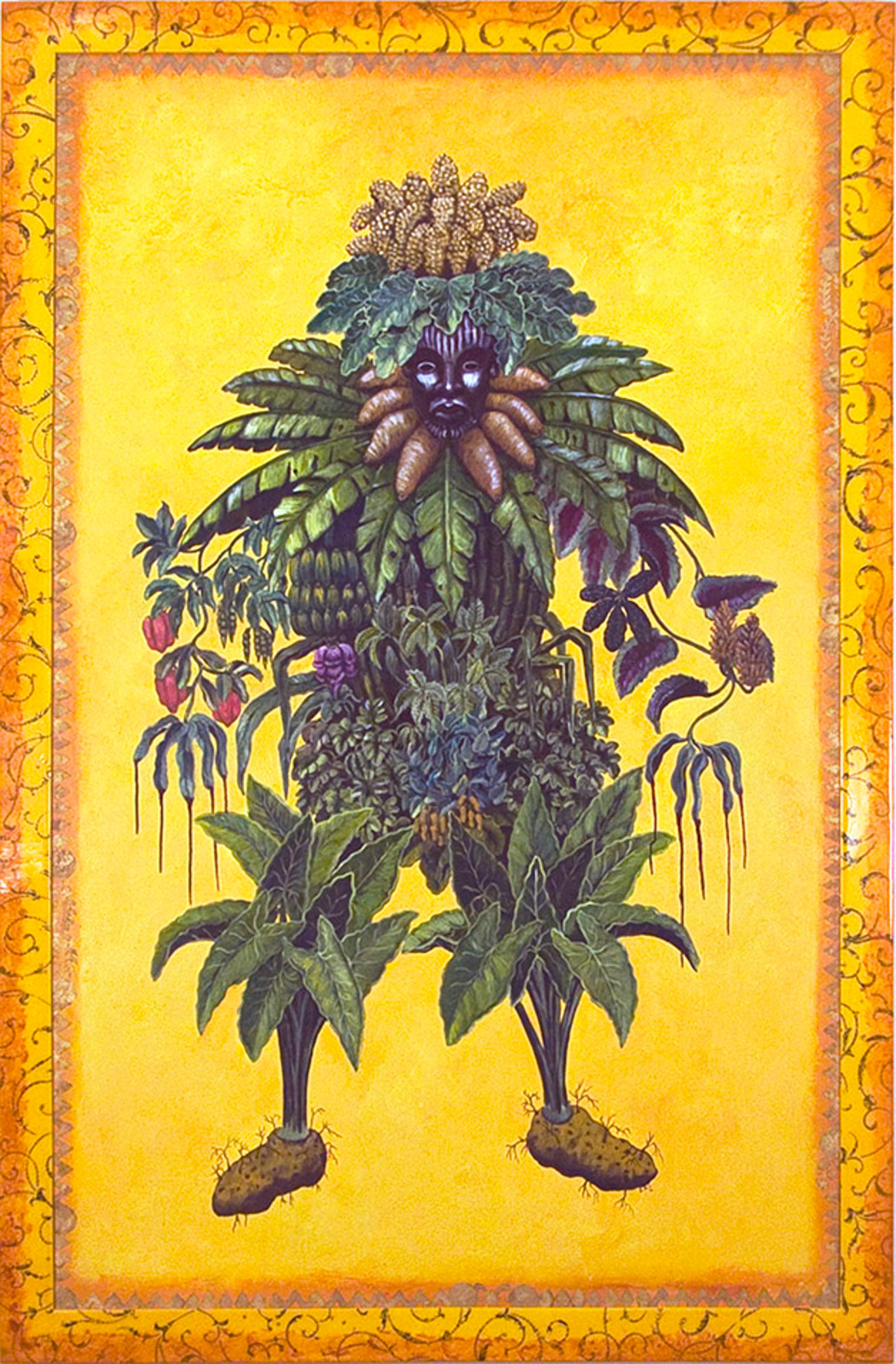

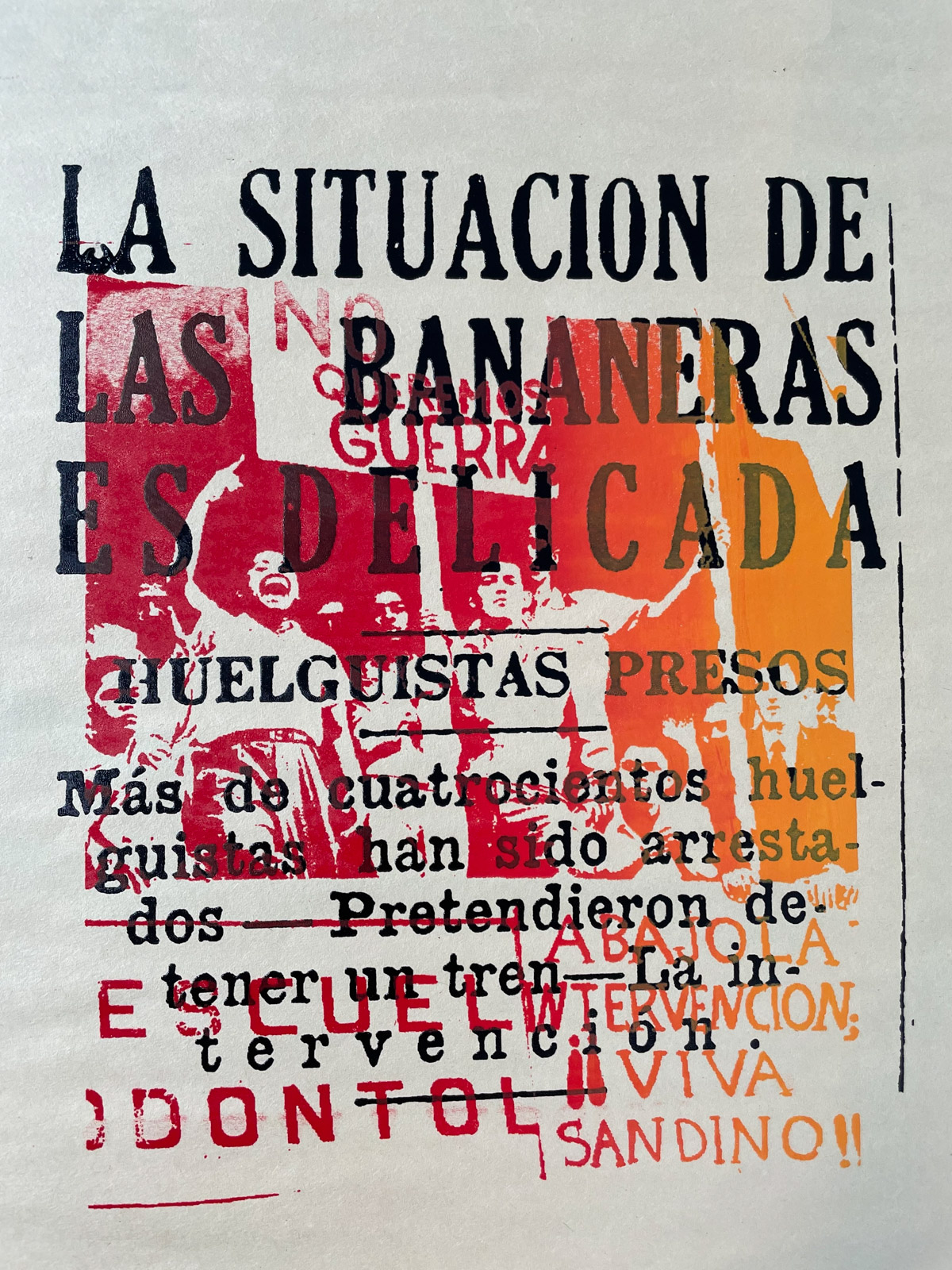

The works included in this section express reflections on the banana industry’s impact on national, cultural, labor, racial and sexual identities. The deep impression made by the banana sector on Latin America and the Caribbean throughout the twentieth century has forged links between the banana industry and the region’s individual, social and political entities.

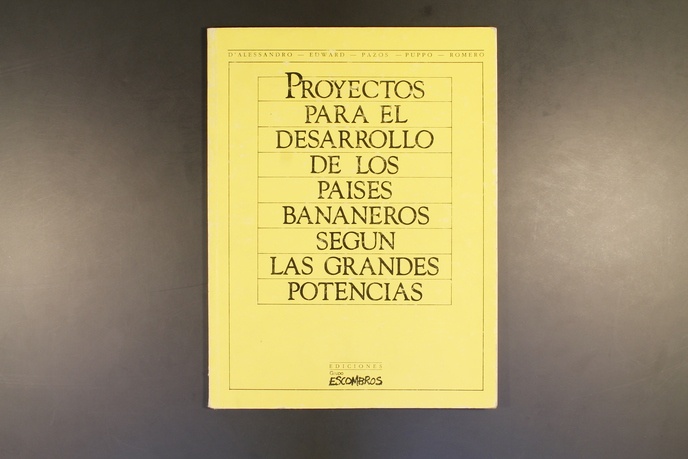

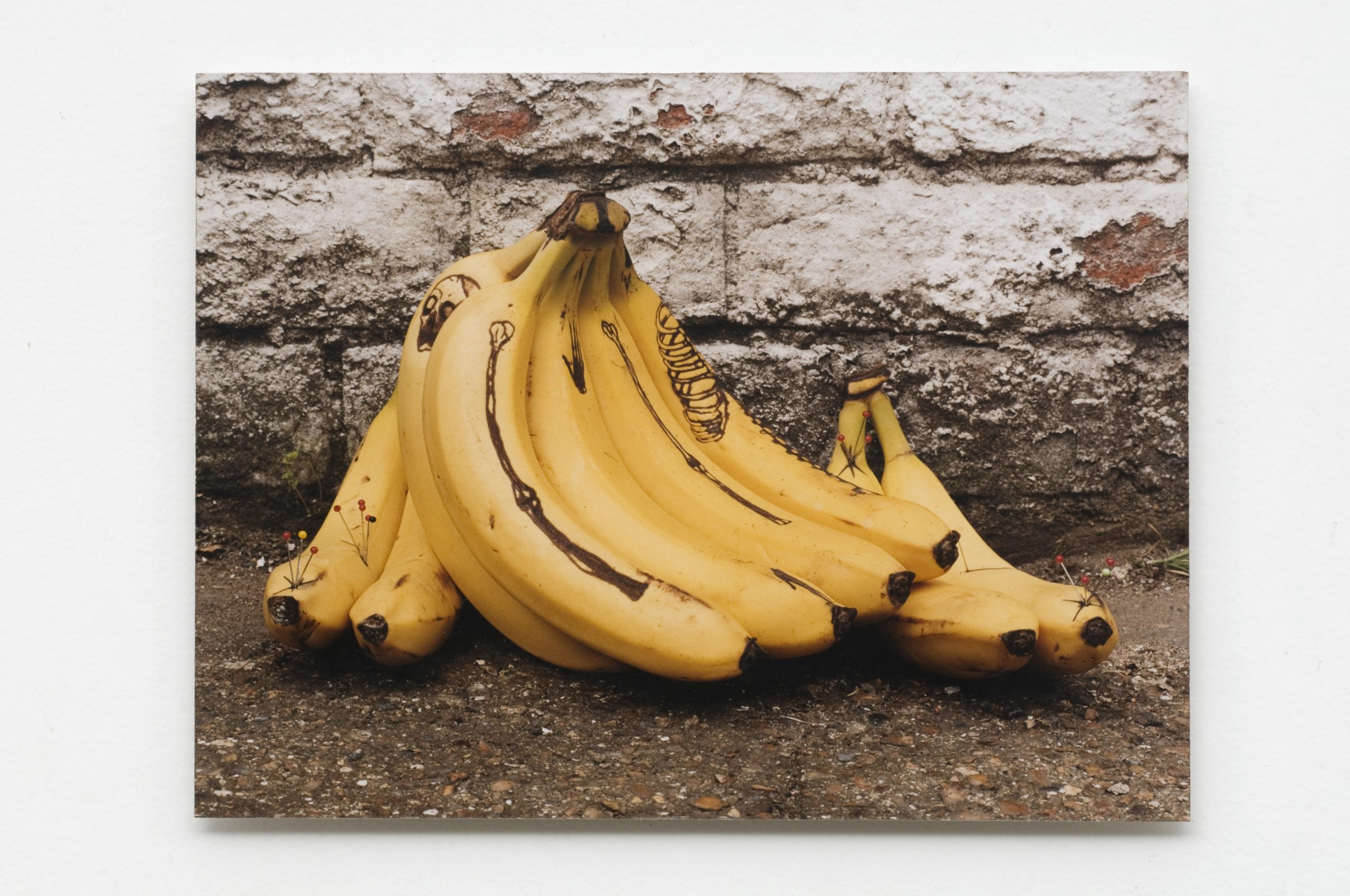

The banana industry functions as a symbol of national identity in the work of artists from countries as diverse as Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Puerto Rico and Uruguay. As it cultivates one of the region’s most heavily exploited natural resources, the banana industry almost literally embodies the concept of the land as nation; this can been seen, for example, in the work of the Ecuadorian María José Argenzio. The weight of the dramatic history of the banana plantations in the development of a collective ethos throughout Latin America is evident in a series of works in which the skin of the banana fruit is tattooed with different inscriptions (Karlo Andrei Ibarra, José Caerols “Yisa” and Tonico Lemos Auad). The term “banana republic” and its universal adoption as an expression to describe any chaotic, corrupt and despotic regime based on the Latin American precedent is addressed by international artists such as Luis Camnitzer.

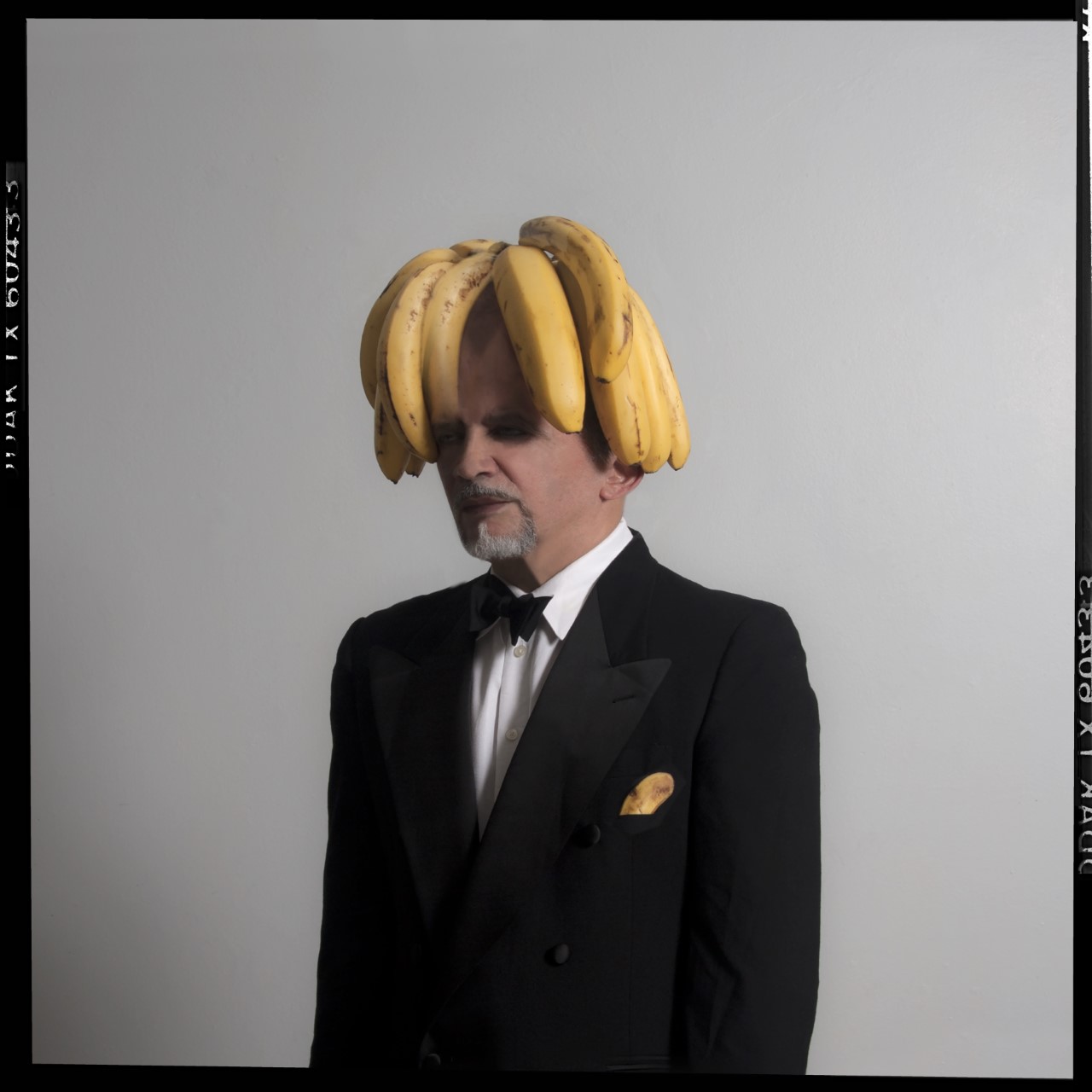

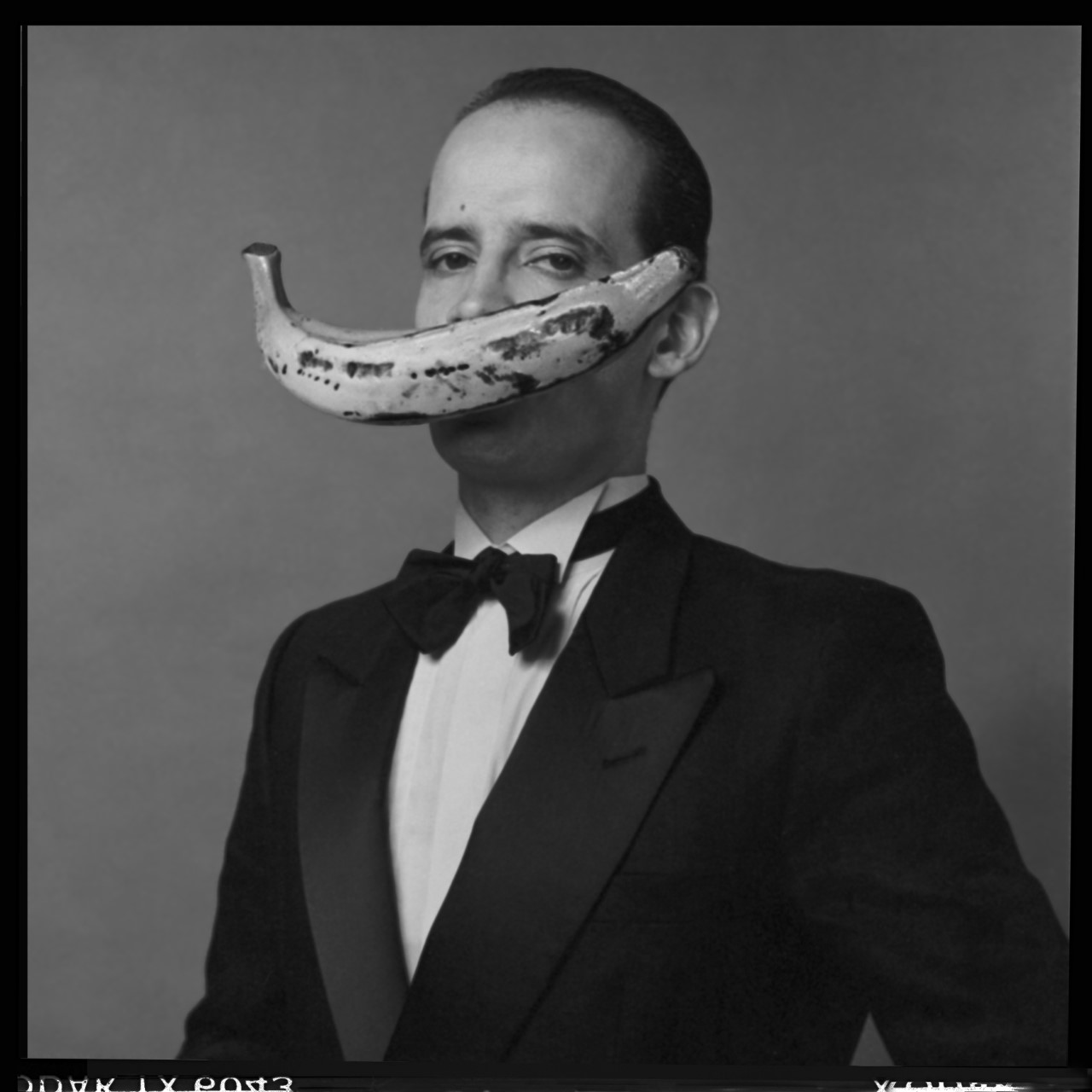

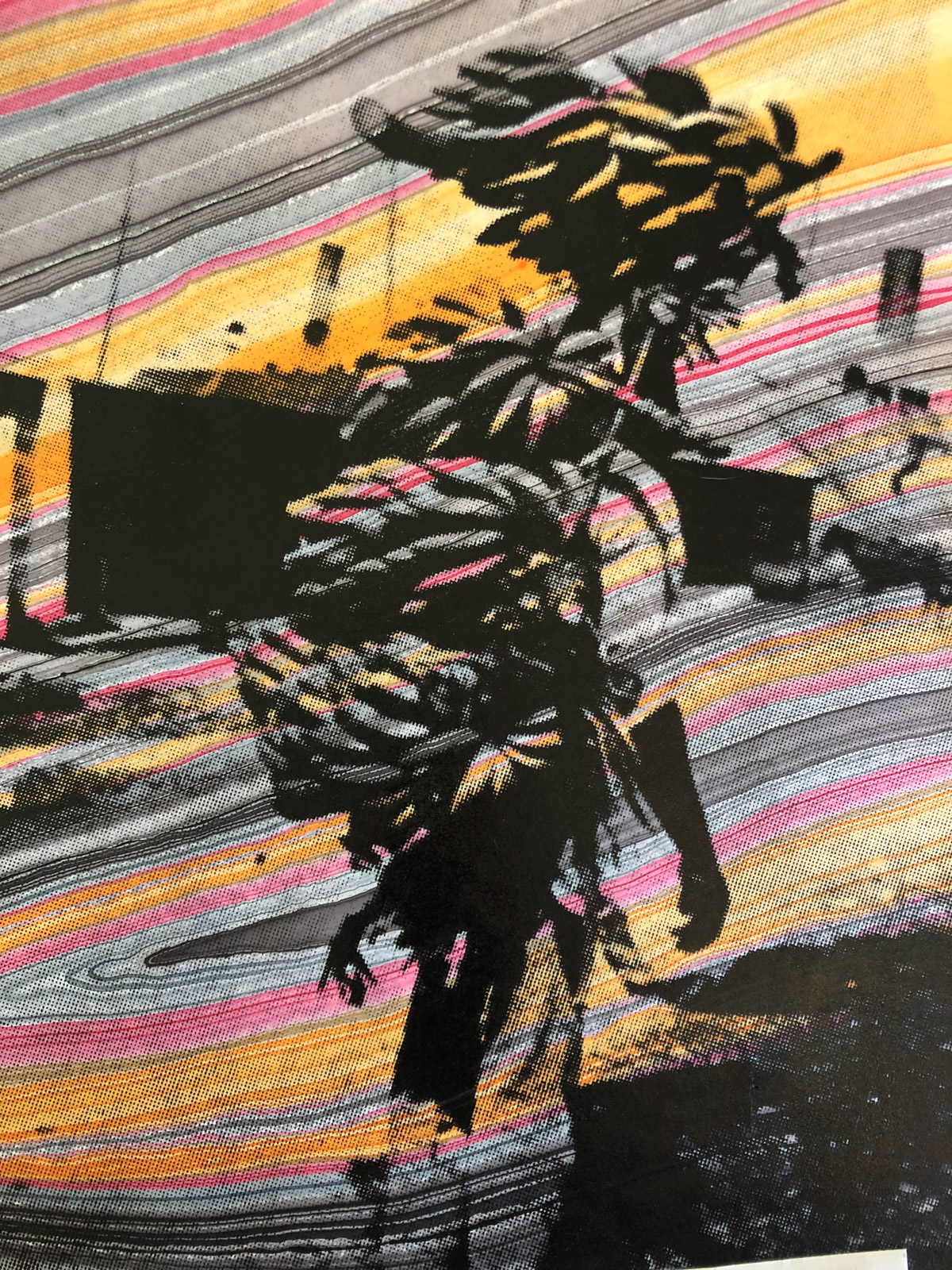

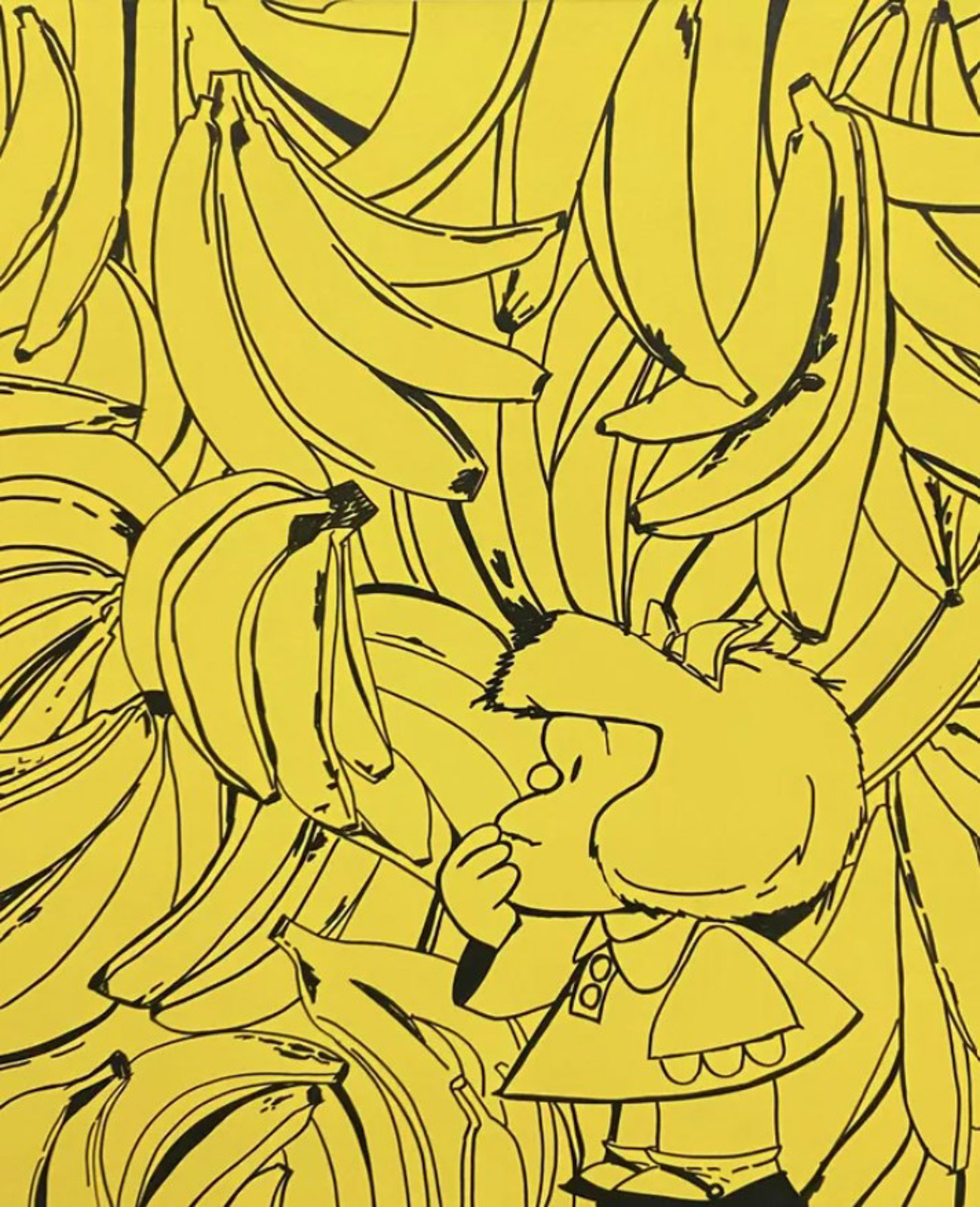

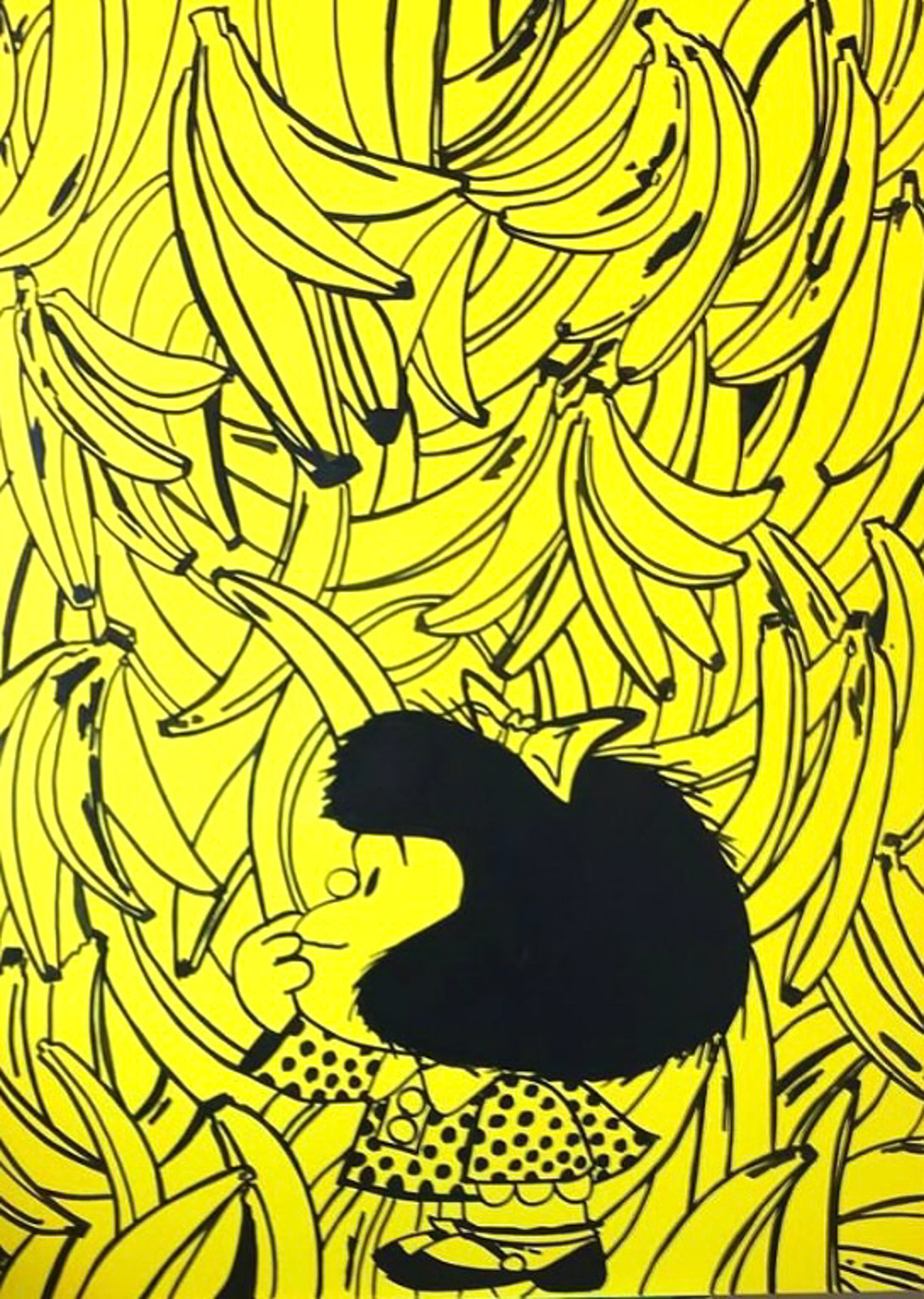

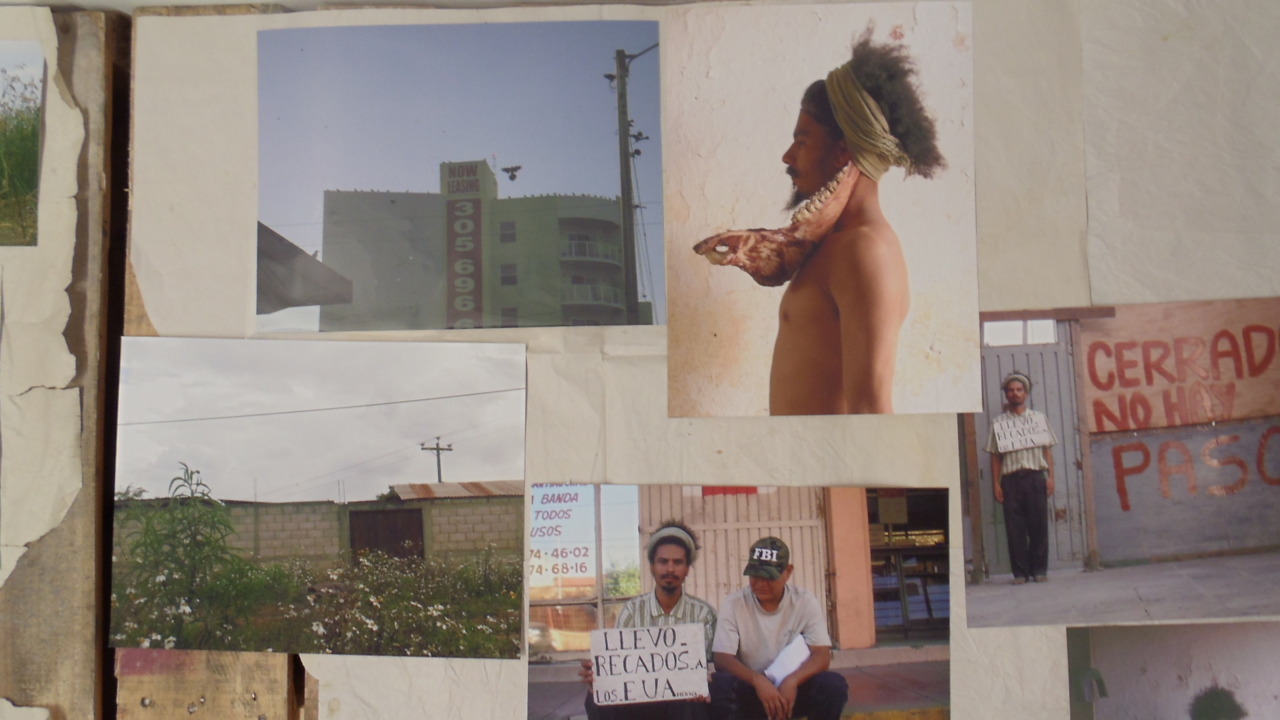

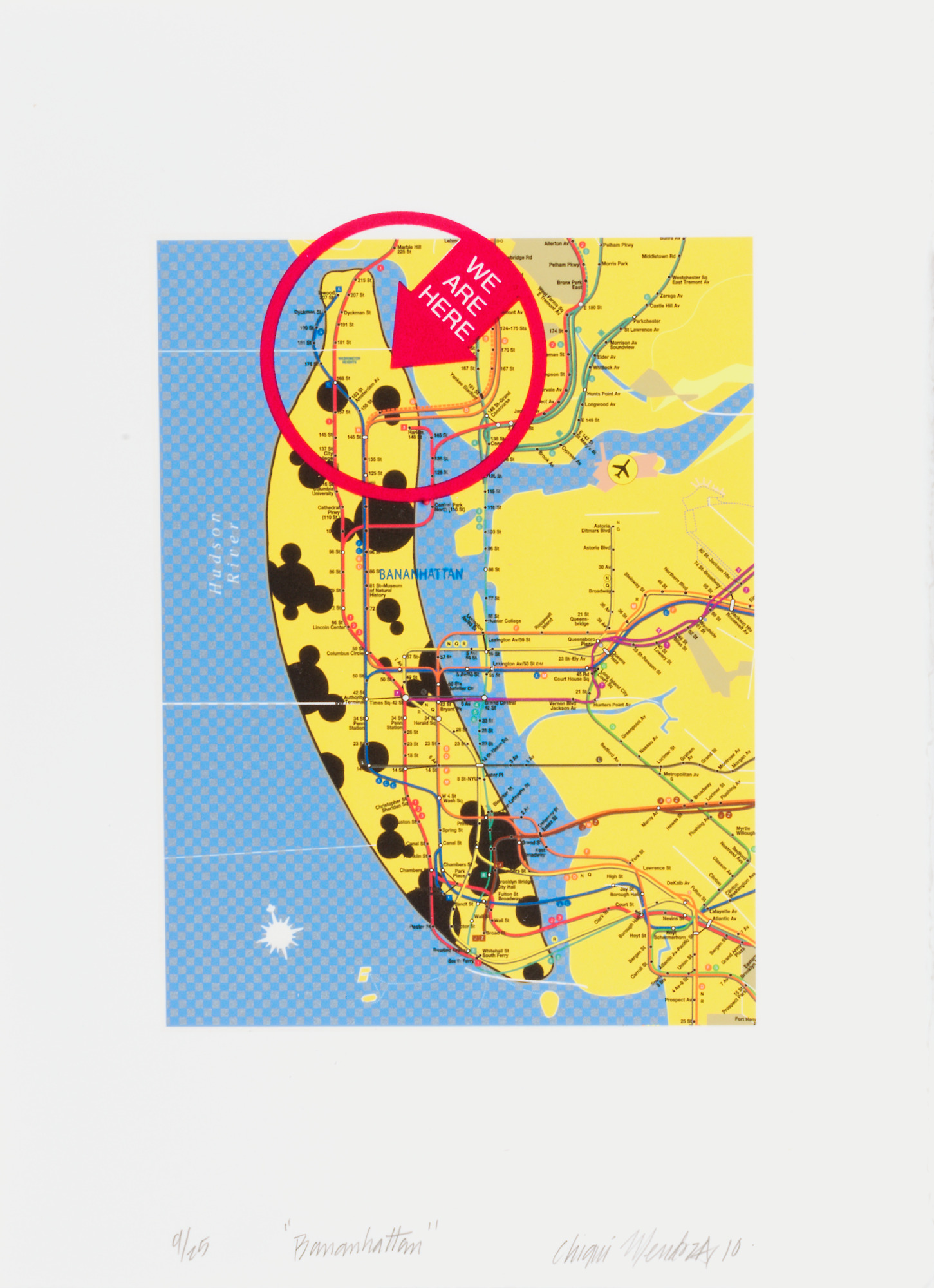

The Latinx identity, a construct that emerged in the United States to denote and recognise the identity of migrants and their descendants, frequently finds itself represented in terms of banana cultivation. In some works, the banana acts in terms of a proud symbol of identity as the legacy shared by millions of migrants of Latin American origin in the United States. By contrast, in other works it is used as a resource to criticise the forced homogenisation of the diversity of Latin American cultures in this country. In the work of Yunior Chiqui Mendoza, the Dominicans and Puerto Ricans living in Manhattan convert the New York island into a banana plantation. For Julio Valdez, the weight of the migrant memory clouds the portrait of his brother, whose face is half obscured by bunches of bananas, while Miguel Luciano assimilates the fruit into global pop culture by turning it into the kind of jewellery flaunted by hip hop stars.

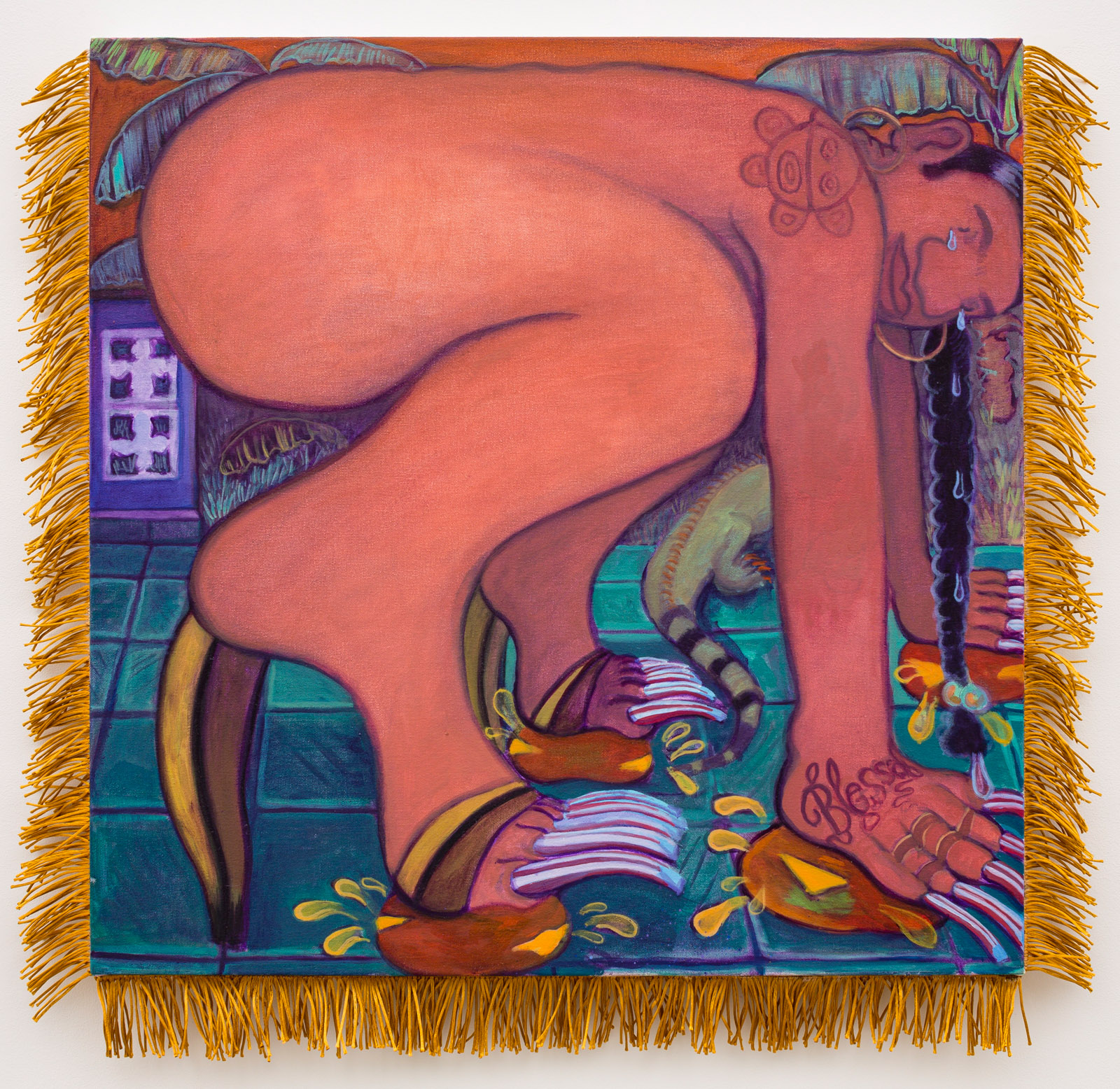

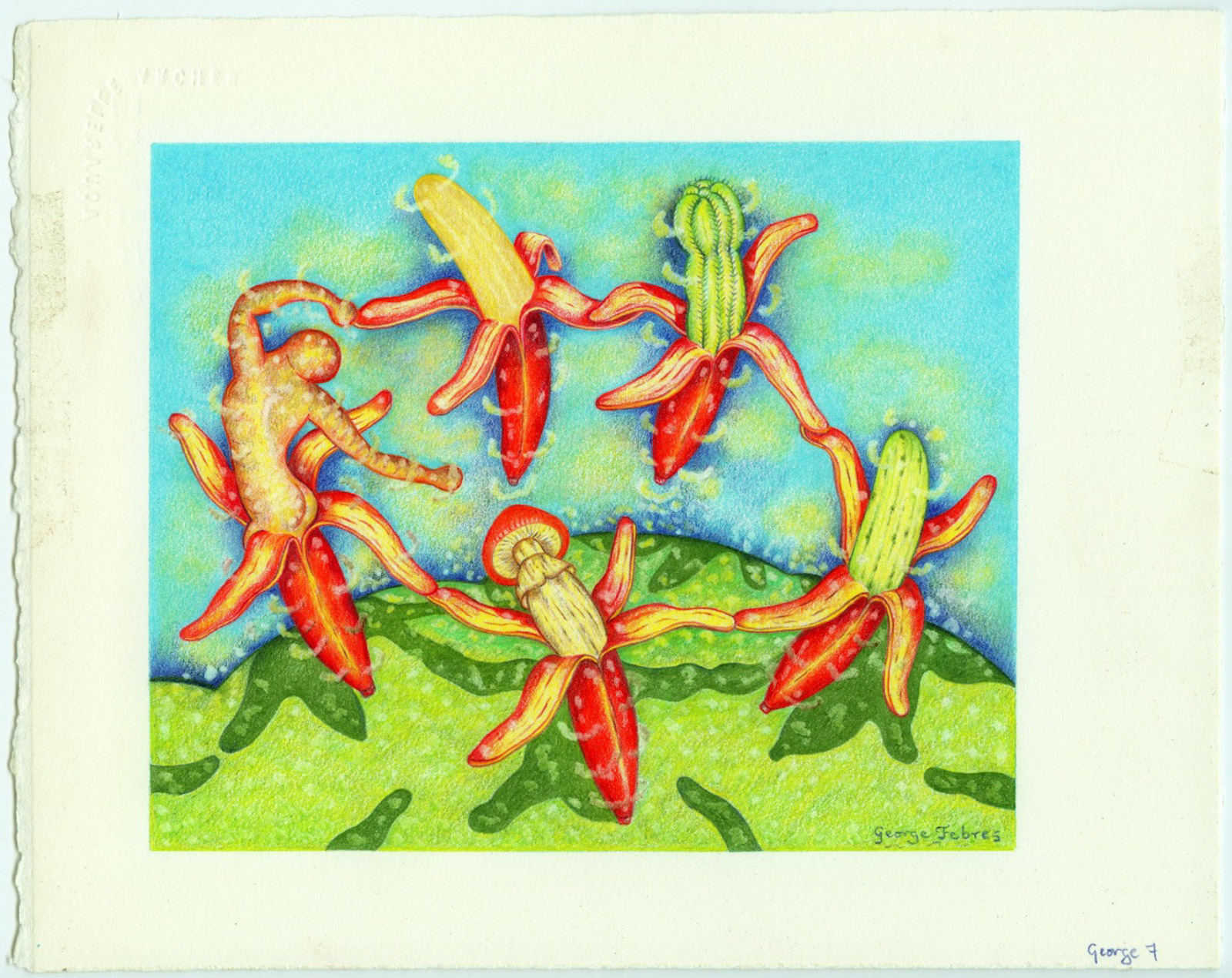

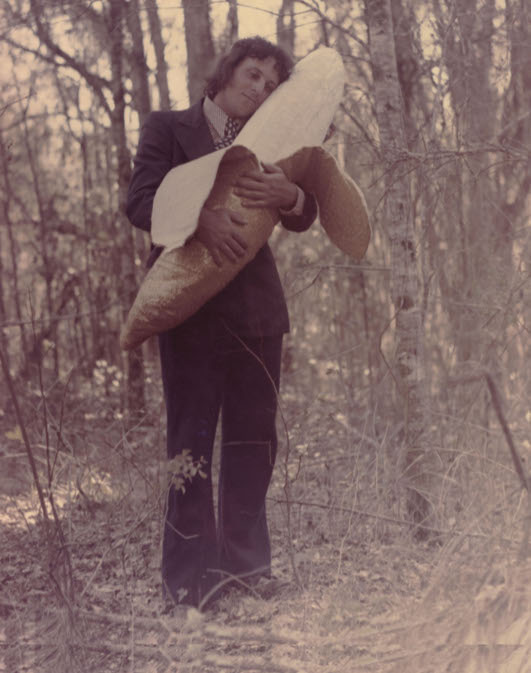

Banana marketing does not escape the traditional allocation of tasks according to gender. Work on the plantations has generally been portrayed as a male activity (think of a bare-chested man wielding a machete), thereby obscuring the work of cleaning and sorting the fruit, which is normally carried out by women.1 On the other hand, advertising of the banana as a food staple has been chiefly aimed at women consumers, as it is assumed that the responsibility of feeding the family mainly falls on women.2 This, added to the sexual connotations ascribed to the banana due to its phallic shape, has also served to turn the fruit into a leitmotiv of reflection on gender identity in many works of art. Victoria Cabezas uses a fluffy, stuffed banana to address the question of the relationship between masculinity and fatherhood from a feminine perspective. In the piece by Roberto Guerrero, the image of a group of technocrats, soldiers and politicians sharing a dinner of green bananas turns the spotlight onto strategies employed by those in power to suppress any type of sexuality perceived as being dissident.

Several of the artists in this section also expose the class-related, racist and sexist prejudices associated with Latin America in the rest of the world, and which often find their expression in the banana, which has become the most universally used and recognised embodiment of a tropical fruit. The filmmaker Helena Solberg-Ladd tells of the detrimental effects of these clichés in a documentary biography of the popular actor and singer Carmen Miranda, muse to the United Fruit Company. In their performance Stuff!, Nao Bustamante and Coco Fusco demolish these stereotypes through a comic deconstruction of irresponsible tourism.

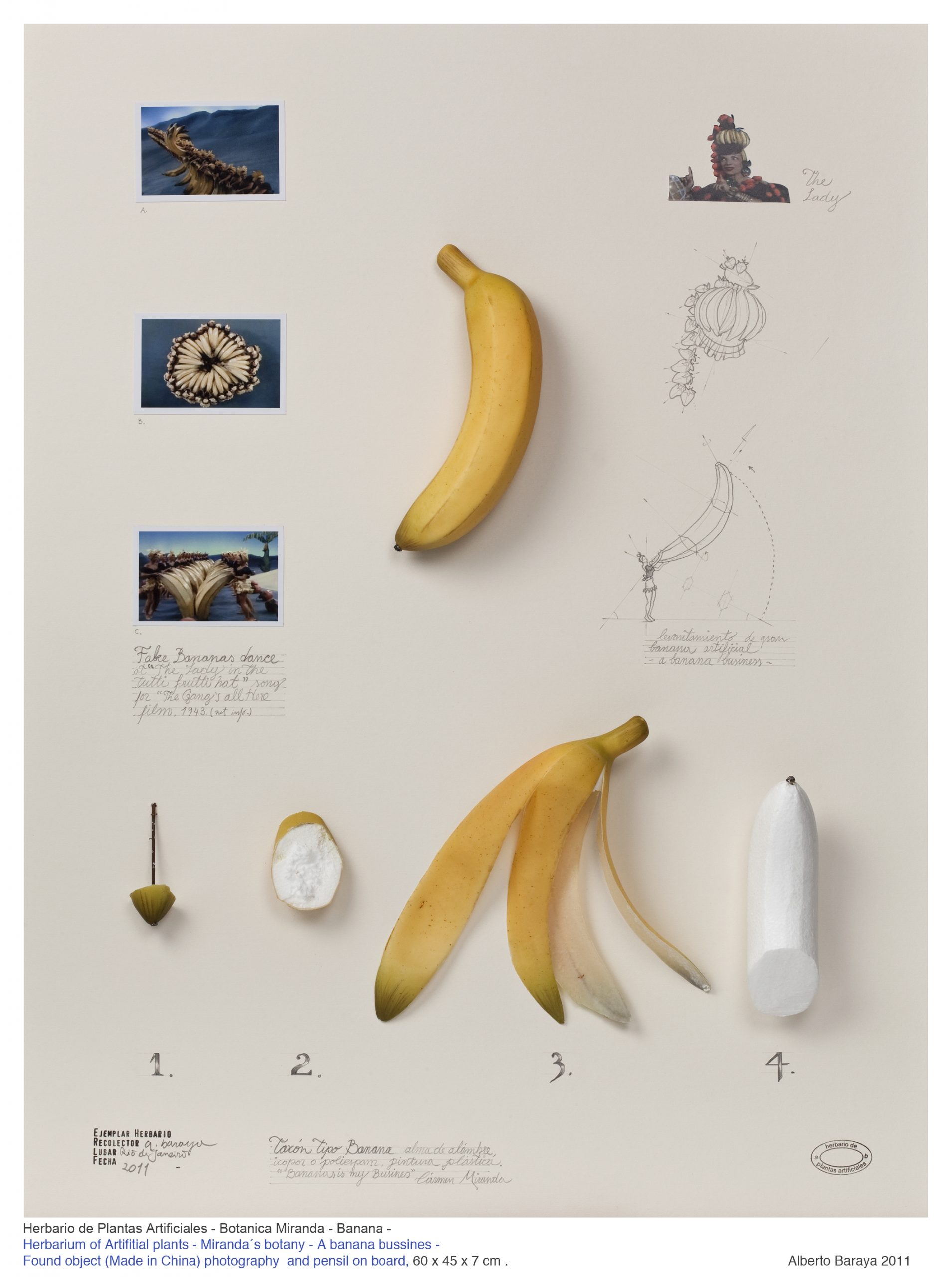

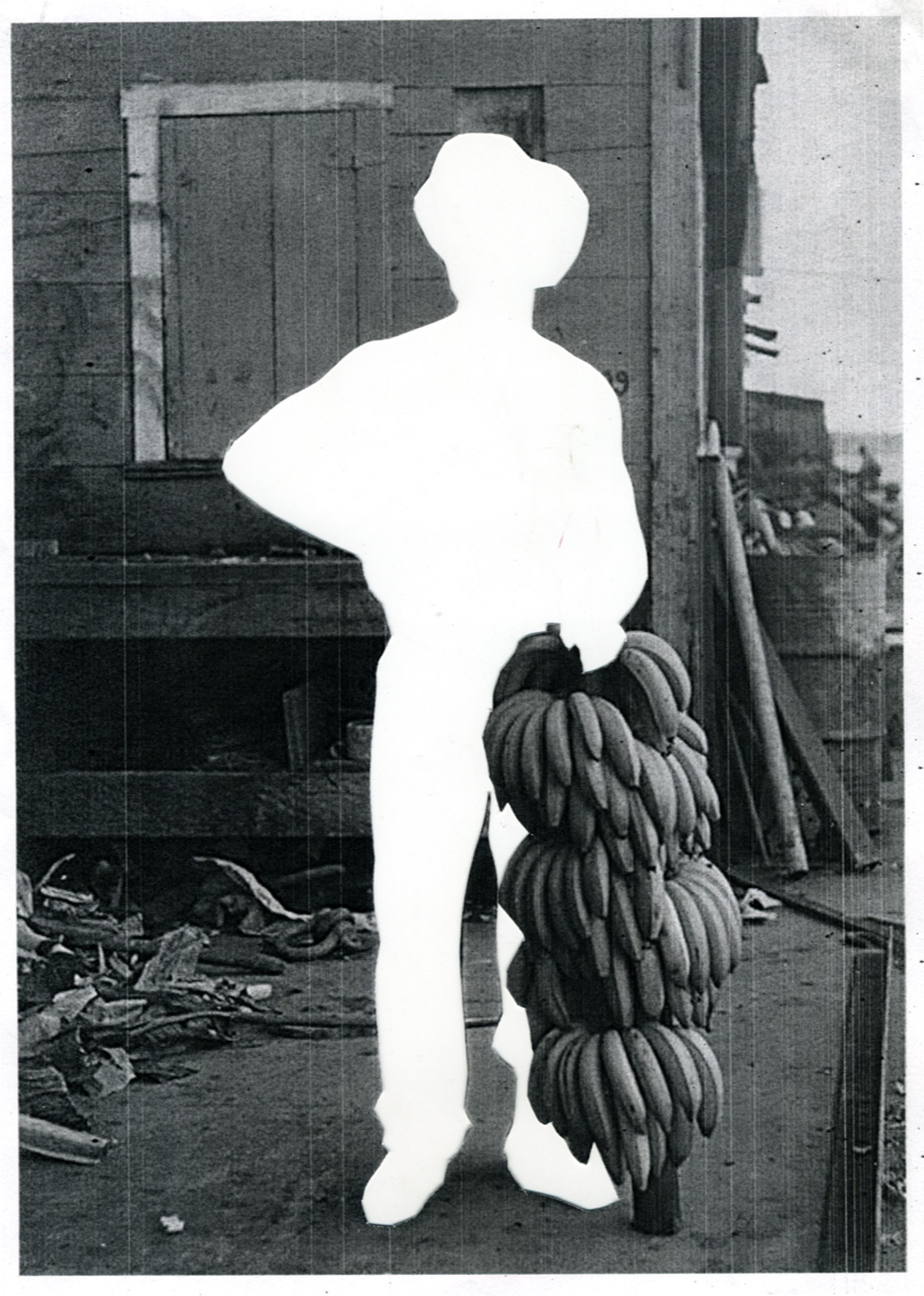

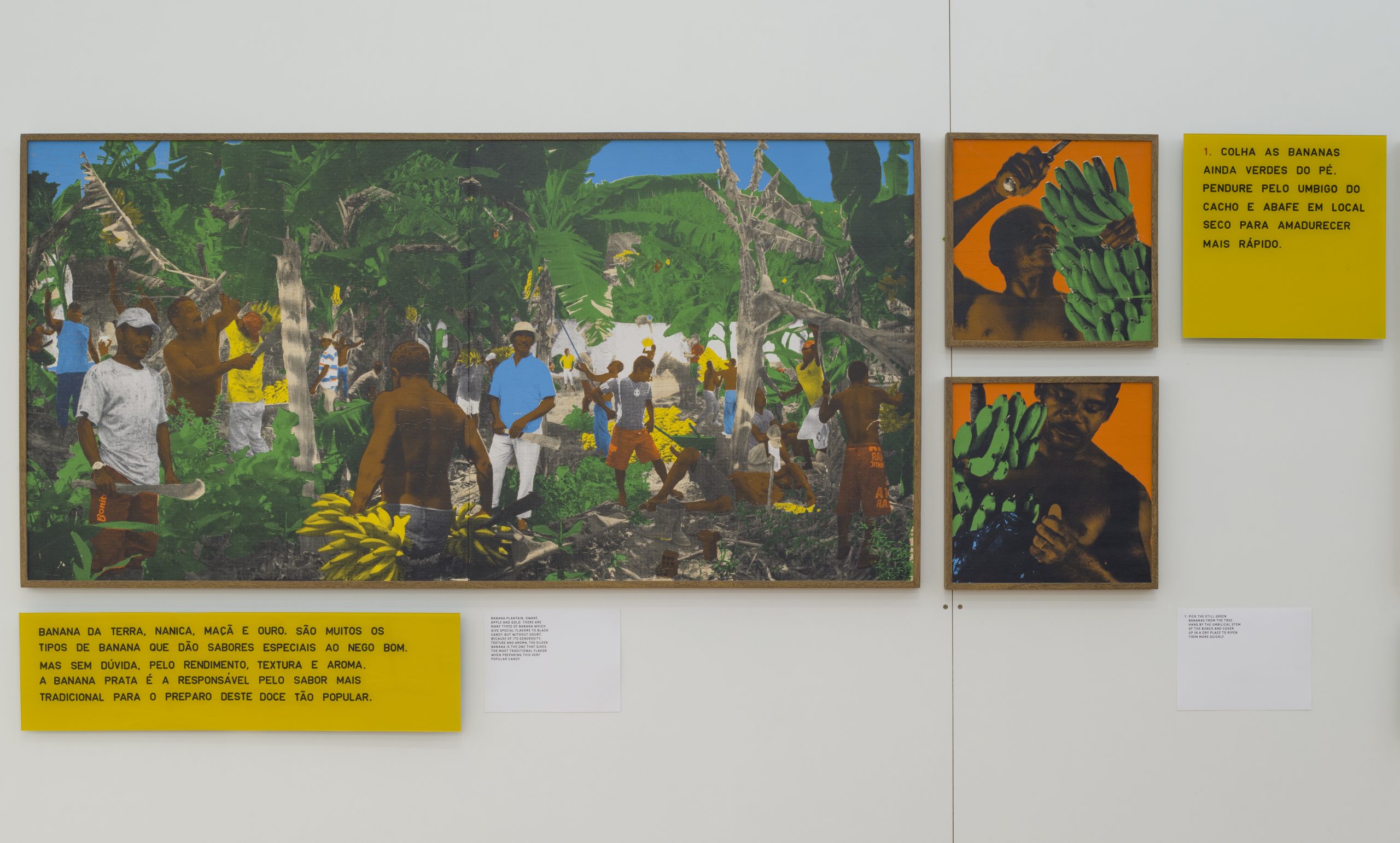

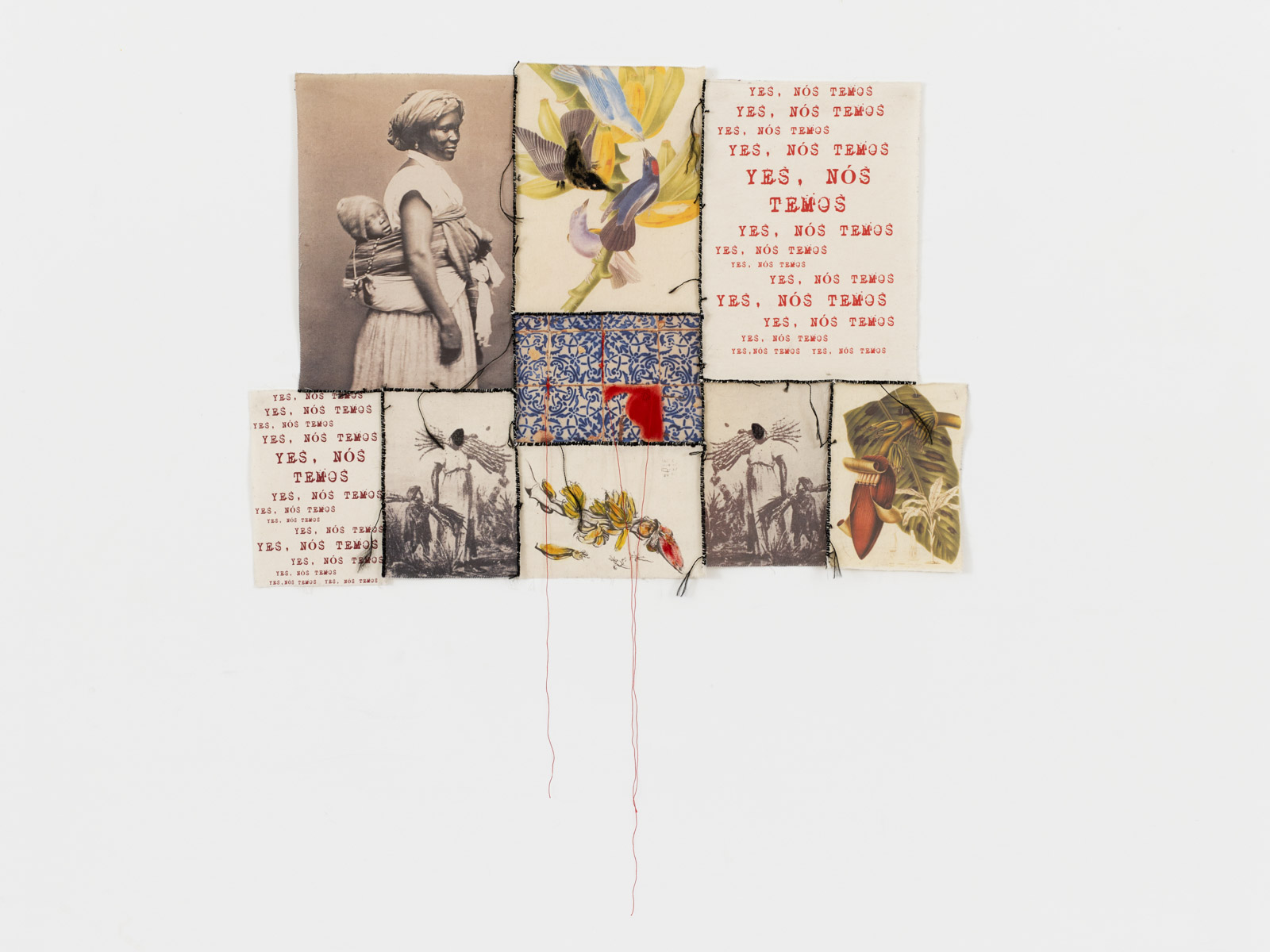

In another group of works brought together in this section, references to the banana plantations provide a springboard for reflections on racism in Latin America and the Caribbean. Alberto Baraya includes a reference to anthroprometric photography, a practice which reached its peak in the nineteenth century, and which aimed to identify criminals and miscreants by measuring their skulls and other body parts, in a work that recalls the discrimination against workers of African descent in the plantations. For his part, Jonathas de Andrade related the harsh working conditions of agricultural workers of African descent in Brazil, with contemporary forms of racism found in popular culture.

Thanks to its presence in the world of gastronomy and in local culture, and to its status as one of Latin America and the Caribbean’s main export products, the banana is now an object frequently present in various reflective exercises. These may focus on regional or national identities (in relation to the region’s socio-political history) or on individual identities (mainly in relation to race and gender). Some demonstrate their acceptance, and others their rejection, of this identification of the banana with Latin American and Caribbean social and individual entities, as the works of many artists address the question of representation by means of this fruit.

1| Please see the chapter “Carmen Miranda On My Mind: International Politics of the Banana”, in Cynthia Enloe, Bananas, Beaches, and Bases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 124-150.

2| Enloe, “Carmen Miranda On My Mind”.